A year removed from the Russian invasion of Ukraine and three years from the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, supply chain disruptions and bottlenecks have eased, remote working is on the decline, travel and entertainment businesses are seeing a strong recovery, consumer spending is steady, and inflation is beginning to come down—a return to some sense of normalcy. The equity markets have been aligned with the recovery and, perhaps hoping for a soft landing, have come back strongly for the past two quarters. Investors returned to growth stocks in Q1 following a surge by value stocks in Q4, providing a remarkably balanced positive swing to equity portfolios over the past six months.

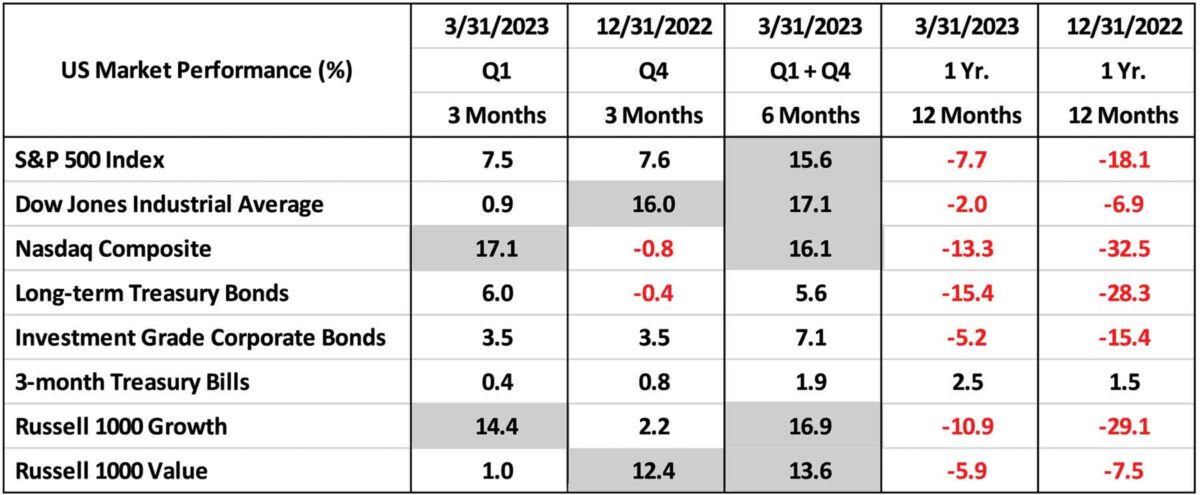

While the performance for 2022 was dismal for stocks and bonds alike, value stocks held up quite a bit better than growth stocks for the year, helping conservative portfolios to more tolerably weather the storm. However, value was again out of favor in the first quarter, with energy, health care, utilities, and financial sectors posting negative returns, down -4% to -6 percent. Growth sectors like consumer discretionary, communication services, and information technology notched the strongest gains, +15% to +21 percent. The year-to-date 2023 and six-month performance rebound is welcome relief, helping investors to recover some lost ground in most portfolios (see Table 1 on following page). This recent pattern of stock market resilience has persisted despite a relatively high inflation rate, multiple bank failures, and a steady drumbeat of recession forecasts.

Table 1. Comparative Market Index Returns as of December 2022 and March 2023

Source: Bank of America Merrill Lynch

Bank Bailouts

The financial sector has been in sharp focus since the March collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), Signature Bank, and Silvergate Capital, the first two representing the second- and third-largest bank failures in US history at the time. SVB was the victim of a bank run triggered by solvency fears of its own venture capital clients. Signature and Silvergate, two of the largest cryptocurrency lenders, experienced their own bank runs resulting from the crypto currency collapse and crypto exchange troubles in 2022. Bankrupt crypto exchange FTX (November 2022) had also been a major customer of both banks. What these bank runs had in common was that each institution was forced to liquidate assets at a loss to raise cash for depositor outflows, a situation exacerbated by the spike in interest rates over the past year.

Because bond values fall when interest rates rise, the Federal Reserve’s nine federal funds rate hikes through March (now ten as of early May 2023) have made fixed income investments (loans and bonds) worth less than maturity values on bank balance sheets. As the federal funds rate has ballooned from an effective rate of 0.08% to 4.65% from February 2022 to March 2023, the value of debt holdings at banks has declined, weakening balance sheets and liquidity reserves if these need to be sold to cover withdrawals. The Fed seems to have overlooked this risk in its annual bank stress testing. Without having adequate reserves to cover withdrawals, the banks collapsed— forced into receivership by the FDIC. The FDIC quickly made all depositors in those failed institutions whole to provide stability to the banking sector, and then sold the failed banks to healthy banks.

The bank runs at these institutions set off a wave of panic among customers of regional banks, while the FDIC has tried to contain the panic contagion. First Republic Bank in San Francisco was hit hardest after the SVB collapse, with a bank run of its own when their well-heeled customer base, many of whom held deposits far in excess of the FDIC’s $250,000 insurance limits, withdrew $100 billion of deposits in the first quarter. The volume of cash moved to other institutions from First Republic was an unsustainable hit to their balance sheet, even with a $30 billion cash infusion from a consortium of eleven large banks orchestrated by JP Morgan and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen. Eventually, First Republic also entered FDIC receivership and was sold to JPMorgan Chase—now taking the title of the second-largest bank failure in US history.

The balance sheet troubles at these failed banks may be just the tip of the iceberg. On average, US banks have had to write down their marked-to-market assets in the form of loans, bonds and mortgages by 10%, while unrecorded losses in held-to-maturity (HTM) assets could total $2.2 trillion in US banks.[1]

The Federal Reserve requires banks and depository institutions to hold a minimum level of reserve cash in their vaults or at the Federal Reserve against their liabilities (demand and checking deposits), currently set to only 10% of those liabilities. This means they can lend out the other 90% to earn a margin on the interest they pay on the deposits. Given these withdrawal reserve levels, it is not surprising that bank runs above 10% can quickly cause a collapse. The problem lies in the HTM assets, which the banks may borrow against at face value, and need not mark to market. In a liquidity crisis similar to that experienced at SVB and First Republic, with the available-for-sale securities depleted, sales of the HTM securities became necessary to meet withdrawal demand. Those sales showed the true value of the HTM assets was tens of billions of dollars less than their balance sheets had indicated. Unable to meet withdrawal demands, the banks were deemed insolvent.

This HTM reporting follows generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) implemented across the banking industry. With the spike in interest rates affecting asset valuations broadly, one can assume that the HTM assets across the US banking industry are overvalued to some extent, and therefore, the banks are not as well capitalized as their balance sheets might suggest.

Withdrawal fears beget additional withdrawals. Mortgages originated in the past decade at yields less than 5%, many close to 3%, generated reasonable income for banks when banks were paying very little interest on deposits. The current interest rate environment has made paltry deposit rates noncompetitive with higher rates paid by money market funds and Treasury bills, so bank balance sheets dominated by low interest rate loans are suddenly getting squeezed by depositors demanding higher returns for their cash. It is a catch-22 for the banks: if they raise deposit rates, net interest margins get squeezed, and if they don’t raise deposit rates, the deposits flee for better returns. New loans made at higher rates will help over time, but for now the bulk of income generated by their current balance sheets is worrisome at best. There will be more bank fallout to come.

Commercial real estate loans may be the next shoe to drop for the banks, as valuations and refinancings are being hit hard by rising interest rates, while Covid-19 pandemic-motivated remote work has negatively impacted office space vacancy rates that have been rising since 2020. Bank loan books are vulnerable to volatility from this sector, with rising loan-to-value ratios and higher interest rates likely to crimp loan refinancings, raising the risk of higher nonperforming loans and loan defaults on the horizon.

As this banking drama plays out, small and regional banks are especially vulnerable and reeling from their own deposit outflows. The perception of extra risk in the small banks has been driving deposits out, especially deposits in excess of the FDIC limits, to safer havens. Consumers are not alone in feeling worried; many businesses hold cash balances beyond FDIC limits out of necessity to manage payrolls and expenses. The flight out of community and regional banks to the perceived safety of money center banks and to money market mutual funds has been dramatic. Money market interest rates north of 4% compare favorably to the negligible bank savings account interest rates of 0.2% on average, according to Bankrate.com. The largest two banks, JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America, continue to offer just 0.01% on deposits. This has accelerated the deposit flows toward higher income-generating accounts, particularly money market mutual funds, which saw assets rise to a record high $5.2 trillion at the end of March as inflows of $304 billion transferred following the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank.[2] Savers pulled money from bank deposits but also shifted money from community and regional banks to money center banks and Wall Street titans.

In the fallout from these bank collapses, large institution beneficiaries included Bank of America, Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs, and Fidelity.[3] Flows to the “too big to fail” banks, Treasury bills, and money market mutual funds will have a detrimental impact on the smaller community and regional banks. Community banks in the US hold roughly 15% of banking industry assets, yet represent 30% of commercial real estate loans, 36% of small business loans, and 70% of agricultural loans.[4] Tightening credit standards and diminished capacity to lend will have a negative economic impact on growth and spending by both business and consumers. Banks will be forced to raise the interest rates they pay on deposits, further squeezing net interest margins and profitability.

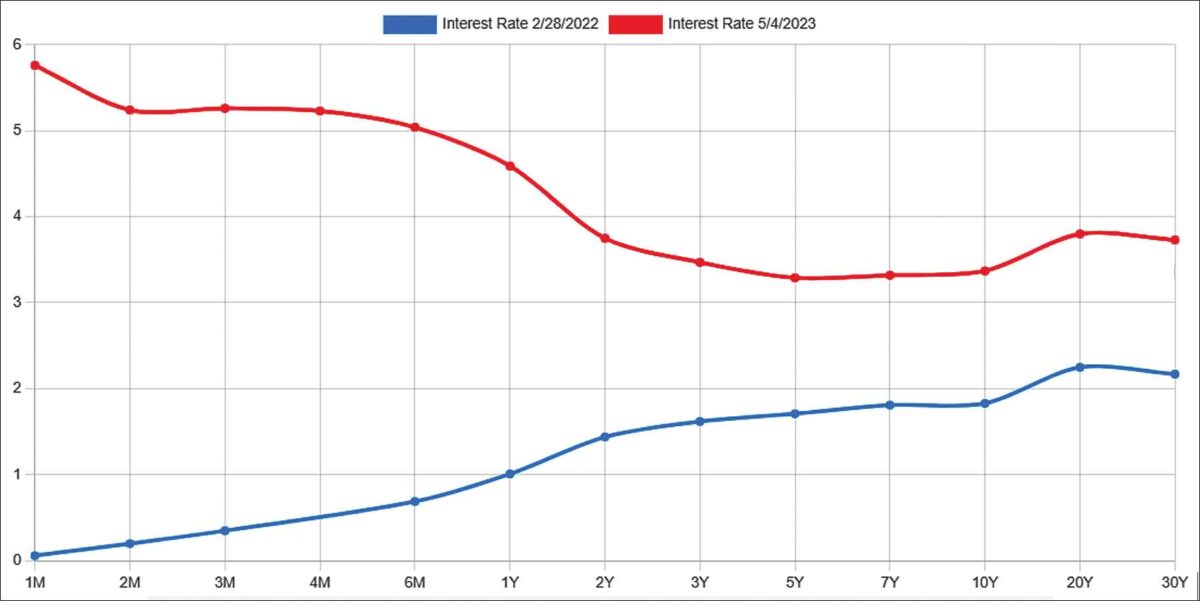

Fed Policy Progress

Including the two quarter-point rate hikes in the first quarter (February and March), and the latest 25-basis-point hike in May, there have been ten rate hikes by the Federal Reserve since March 2022, totaling 5.00 percentage points, the fastest tightening cycle since the 1980s. The current range for the federal funds rate (May 2023) is 5% to 5.25 percent. This series of Fed rate hikes has had a dramatic impact on the US Treasury yield curve, which has inverted steeply over the last year (see Figure 1). The implications have been felt beyond the banks’ interbank lending mechanism, with consumers facing spiking rates for mortgages, home equity loans, credit cards, auto loans, and personal loans. Banks are also tightening lending standards. The higher cost of borrowing will cause consumer borrowing and spending growth rates to trend lower going forward. Business growth will also be hampered which likely will crimp hiring, driving up the unemployment rate.

The shape of the yield curve, however, indicates the market is expecting the Fed to have to cut rates in the future, as long-term rates are markedly lower than short-term rates. The yield curve inversion is forecasting that high short-term rates will not persist. Demand for bonds should rise in an attempt to lock in current yields that are expected to fall in the future. This demand should drive up prices for bonds, pressuring rates. The shape of the curve also implies the market is expecting that the Fed’s course of action will be successful, resulting in lower inflation in the future.

Figure 1. US Treasurys Yield Curve (%)

Source: ustreasuryyieldcurve.com

Source: ustreasuryyieldcurve.com

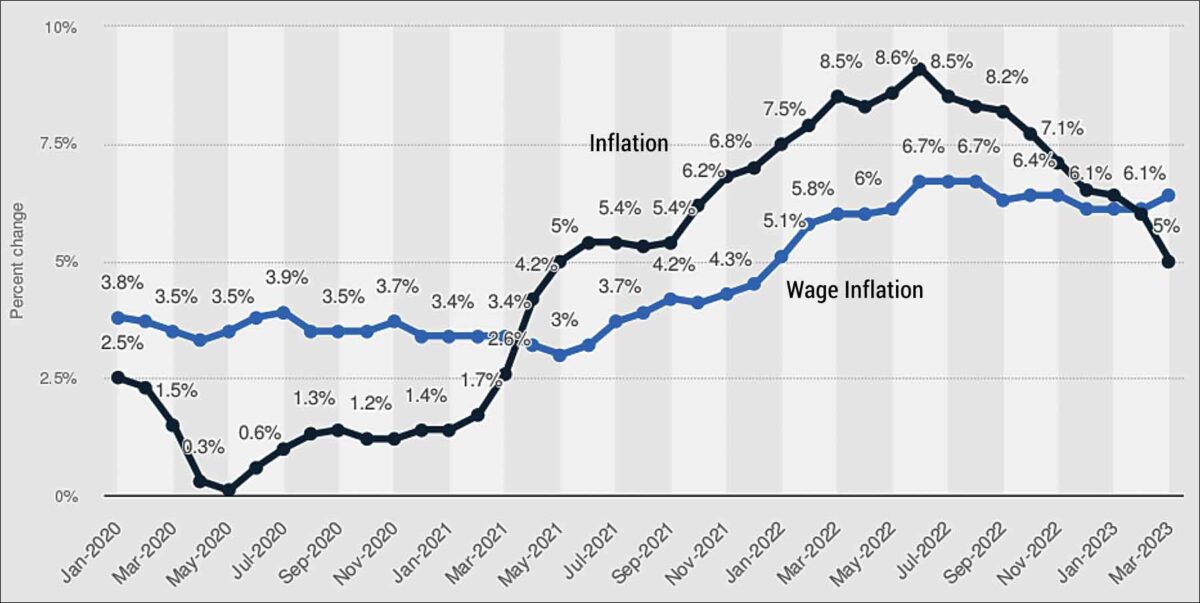

Higher inflation and higher interest rates have not yet had an impact on employment levels. The unemployment rate has also been stubbornly resilient and near all-time lows again at 3.5% in the March report. This is considered a level of full employment by the Fed. The number of job openings has been coming down however, declining from two openings for every job seeker in December (11.2 million job openings) to 1.6 jobs per seeker in March (9.6 million job openings) while the number of unemployed has risen from 5.7 million to 5.8 million over this period. (see Figure 2).[5] At the same time, wage inflation has been rising. The rate of wage growth hit 5% at the start of 2022, up from the mid-3% range, and has been steadily above 6% for the past 12 months, notching 6.1% in March (see Figure 3).[6] The tight labor market, difficulty hiring, and demand from employees for wages to keep up with inflation are all factors in rising wages.

Figure 2. Total Job Openings Relative to Job Seekers

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Figure 3. Inflation Rate and Growth of Wages in the US, January 2020 to March 2023

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics; Federal Reserve Bank; US Census Bureau

©Statista 2023

Additional Information: United States; January 2020 to March 2023

Private sector job growth increased by 145,000 jobs in March, below the 210,000 estimate and down from 261,000 in February. Average hiring in Q1 was 175,000 jobs per month, a decline from the Q4 2022 rate of 216,000 jobs per month, according to ADP’s National Employment Report. The US Department of Labor released total nonfarm payrolls for March, which combines private and government hiring, and it is also showing that job growth has been declining steadily over the quarter. January added 472,000 jobs, February 326,000 jobs, and March 236,000. This is an average increase of 345,000 jobs per month for Q1, but down 38.5% from the year ago Q1 2022 average of an additional 561,000 jobs per month.

The headline Consumer Price Index (CPI) numbers have declined from 8.9% in June 2022 to 5% in March 2023, below the wage inflation number, with the Fed policy seemingly countering the wage-price spiral effect of rising wages. In this economic theory, rising wages increase demand for goods and services because wage earners have more money to spend. However, these higher wages also increase the cost of production and transportation. Increasing costs of production and increasing consumer demand tend to force companies to raise prices, which in turn causes employees to demand higher wages to keep up. This spiraling inflationary pattern continues until the government enacts policy to stymie the spiraling effect. With CPI dropping noticeably since the mid-2022 peak, the pressure for wage inflation is likely to taper off as well.

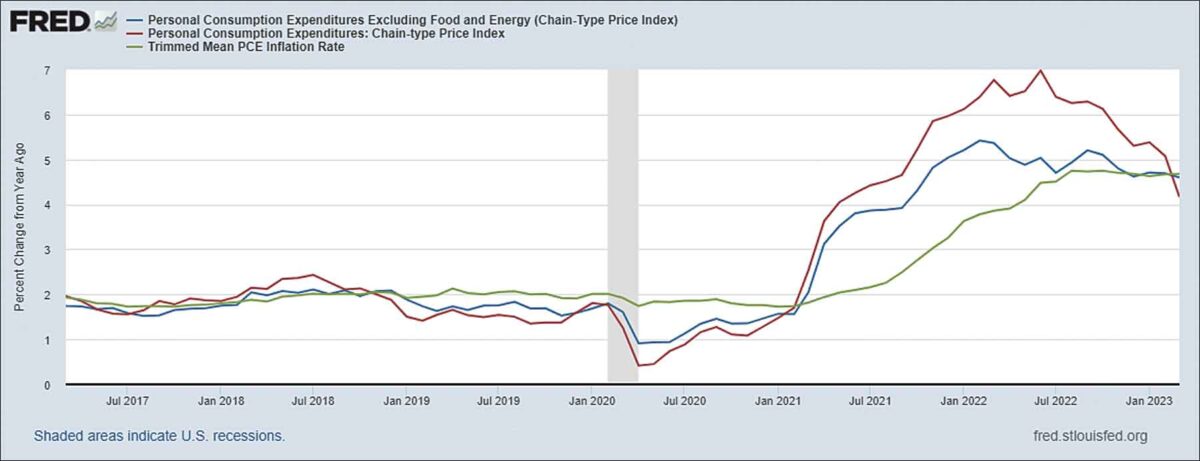

The Fed focuses more on the change and level of the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) index than the CPI. Three measures—PCE, PCE excluding Food and Energy and the Trimmed Mean PCE—are instructive in predicting Fed actions. The three congressional mandates of the Fed are the achievement of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates. The Fed is raising interest rates to bring down inflation, and hoping for only modest impact to the current full employment level. Rising rates will have a lagged effect on hiring and most probably induce a higher level of unemployment. Despite Fed actions to date, the Trimmed Mean PCE level (trimmed of high and low spikes with in the PCE component metrics) has not changed dramatically since last August, staying in the range of 4.7% (see green line in Figure 4). This leads to an assumption of continuing rate hikes until inflation levels begin to subside.

Figure 4. Comparison of Personal Consumption Expenditure Indexes

Source: BEA; Dallas Fed

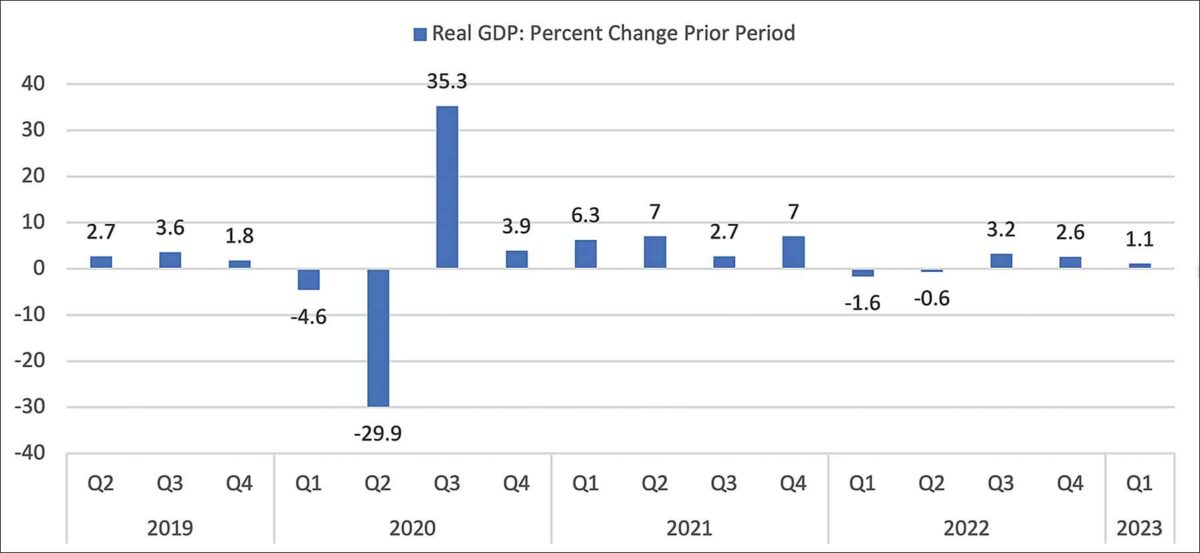

These dynamics are beginning to impact real GDP growth, which continues to show positive momentum though at a slowing rate over the past three quarters. Real GDP posted a +1.1% change for Q1, down from 2.6% in Q4 and 3.2% in Q3. Adjusting for the 4% inflation factor reducing real GDP, nominal GDP growth in the first quarter was 5.1 percent. The increase for the quarter reflects strong consumer spending particularly on automobiles, food, healthcare and travel. The consistency of the consumer spending pattern has been surprising in the face of a possible recession. Recessions are characterized by periods of weak growth of domestic output, income, and employment and are generally measured by two consecutive quarters of negative real GDP growth, as can be seen in the first two quarters of 2022 in Figure 5. However, the decline in GDP growth in 2022 was not officially a recession according to the National Bureau of Economic Research, because of other factors including strong job growth at the time.[7]

Figure 5. US Real Gross Domestic Product Growth

Seasonally adjusted annual rates. Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

Resulting Recession or Soft Landing?

With unemployment low, job openings high, positive economic growth, strong consumer spending, persistently high inflation, and a recovering stock market, it would not be surprising for the Fed to continue raising rates in June and to leave these rates higher for longer. The market is hoping the Fed is close to the end of its tightening cycle, especially in light of the banking sector turmoil, but the Fed’s focus on fighting inflation will continue until it brings inflation back to its long-run 2% goal. As for the banks, the problems with their balance sheets have been compounded by the rapid rise of interest rates and poor management of the liquidity risk it created. Another Fed rate hike or two may continue to negatively affect the shrinking net interest margins at banks already in play. Banks will need to continue to adjust their balance sheets, manage the net interest margin quandary, and the FDIC will need to stay ready to intervene. Raising the FDIC insurance limit above $250,000 would help assure depositors. Larger, better-capitalized banks will absorb the smaller and weaker ones, a healthy strengthening mechanism as the banking industry adjusts to a higher rate environment. The prospect of a new banking crisis is certainly cause for concern.

More than likely, the Fed will overshoot its inflation objective with its rate hikes due to the lagging impact of the change in interest rates. The impact will bring about the slowdown of hiring, restricting economic growth and raising unemployment levels required to bring down inflation. A hard landing may be unavoidable. The Fed’s actions to date will continue to impact inflation, earnings, employment, and GDP growth for years to come, with a recession a likely result late in 2023 or 2024. A soft landing, taming inflation without hurting employment or growth, seems a stretch, but the slowdown is inevitable.

The downturn may also be short-lived and shallow, and stocks are likely to react favorably when the Fed ultimately eases its monetary stance, cutting interest rates. When the Fed does pause its federal funds rate manipulation, one would expect some period of time to pass before reversing direction to let the record-setting interest rate tightening cycle do its job. Confirmation of a recession down the road may be the catalyst to prompt Fed rate cuts, but we are not predicting that action in the near future.

Eventually, Fed policy action should provoke a decline in interest rates and inflation over the next two years, which would provide economic support for stocks. Holding a well-diversified portfolio, including a mix of both defensive and growth-oriented stocks, is a reasonable investment approach to current market uncertainty. Defensive stocks are likely to hold up better if the market turns down. While it is impossible to time the market’s next upturn, we recommend clients look for opportunities to add to positions that are more likely to benefit from the more positive market environment which will inevitably come. The stock market generally will anticipate the end of a recession long before it is apparent.

Our advice, as always, is to stay invested through the market cycle, to not try to time getting in and out of the market, as the best way to participate in long-term economic growth and asset appreciation. If you have any questions about how the matters discussed here could impact your portfolio, we encourage you to continue the discussion with your portfolio manager.

Robert B. Sanders, CFA, Senior Vice President