With the pandemic subsiding and economic growth reaccelerating, a Bloomberg survey of economists expects US real GDP to grow a robust 6.6% this year and 4.1% next. The economy (as measured by real GDP) is expected to have surpassed its pre-pandemic peak in the second quarter of 2021. The S&P 500 Index returned a strong 14.4% through the first half of the year to close at a record high. Pent-up demand and federal stimulus funds have meant that demand for goods and services has recovered much faster than supply. Businesses can’t hire workers fast enough and they’re struggling with supply chain bottlenecks. Strong economic conditions drove the Consumer Price Index (CPI) up 5.4% year-over-year in June, following up 5.0% y/y in May. While many economists had been expecting some inflation, these inflation statistics were higher than most of them, including many Fed officials, anticipated.[1] The CPI excluding food and energy was up 4.5% y/y in June, reaching its highest level since 1991.

The capital markets already seem to have taken the brunt of recent high inflation statistics in stride. Reasoning that the burst of inflation is primarily caused by the sudden economic reopening compared to depressed year-ago prices, coupled with temporary stimulus measures, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell has described the inflation as transitory. At present, real bond yields, that is, bond yields after deducting inflation, are negative. If bond investors expected higher inflation to continue, bonds would most likely be priced to incorporate the expected loss of purchasing power, although negative real yields also likely reflect an abundance of money in the financial system. While inflation could still grind down investors’ enthusiasm, it is most likely on a decelerating, manageable trend. According to one analysis, 55% of the increase in the June CPI came from products and services that have been lifted by short-term supply- demand imbalances.[2] These include used cars, lodging, airfare, and food away from home. That still leaves 45% of the increase stemming from other sources. A one-time change in price levels is probably manageable — inflation would become more problematic if it persisted. The pace at which inflation comes back down and where it settles remain open questions, however.

Beyond 2022, we expect US real GDP growth to settle back to where it was before the pandemic. The inflation rate over the next 10 years will probably be higher than it has been over the last ten, but not by much. Apart from the temporary factors driving inflation higher in the near term, many market observers look to changes in fiscal and monetary policy as reasons why inflation may be structurally higher in the years ahead. Attitudes towards fiscal and monetary policy have changed in recent years, but even so, we don’t think government policy will keep inflation at levels that would be problematic for the economy or for markets.

Attitudes Towards Fiscal and Monetary Stimulus Have Changed

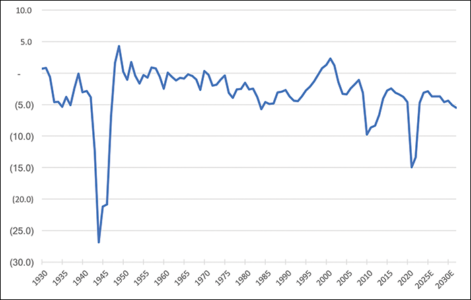

As can be seen in the chart on page 4, Federal deficits have increased either by increasing spending or by reducing taxes under almost every US president since Truman. The Obama administration ran annual deficits of up to $1.5 trillion a year to help the US recover from the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-2009. Operating deficits had been reduced to $500-$600 billion by the end of his tenure, only to be driven back towards $1 trillion under President Trump.

The COVID-19 pandemic saw fiscal spending bills totaling about $6 trillion beyond the country’s operating budget, mostly to be spent over a two- to three-year window to backfill lost economic activity. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the federal deficit is expected to hit $3.0 trillion this year, but then drop significantly, averaging $1.2 trillion a year from 2022 to 2031.[3] The CBO projections take into account enacted legislation, but do not factor in any legislation under consideration.

The heightened level of deficit spending certainly reflects a new attitude, emboldened by the deficit spending over the prior ten years which, despite much anxiety, did little to raise inflation, threaten the federal government’s credit worthiness, or undermine confidence in the value of the US dollar. US Treasury yields remain well below their average levels of the past ten years, and the US Dollar Index remains above its average rate over the past ten years.

Initial pandemic stimulus reflected rare Congressional bipartisanship in the face of certain calamity, conditions which are less likely to recur under more normal economic conditions. The latter part of the $6 trillion in economic stimulus, some $1.9 trillion, occurred under unified Democratic leadership of Congress and the presidency. Most political prognosticators see the Democrats losing at least one house of Congress in 2022, making increased deficit spending that much less likely at least in the near term. President Biden may get an infrastructure bill through Congress, but even so, the bill is likely to call for an increase in spending of $200 billion or so per year over 10-15 years — significant, but not on the order of magnitude prescribed over a short period to address the pandemic. Despite a greater tolerance for deficit spending in Washington, political tensions are likely to act as a constraint on further spending, at least until the next economic crisis.

US Federal Deficit as a Percentage of GDP

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve; Projections: Congressional Budget Office

Attitudes towards monetary stimulus have shifted as well, and for the same reasons they have shifted regarding fiscal stimulus. During the Great Financial Crisis and its aftermath, many economists and market participants were concerned that the Fed’s Quantitative Easing (QE) programs would spur runaway inflation. When QE didn’t lead to significant inflation, and inflation even chronically undershot the Fed’s own target of 2%, observers became much more comfortable with easy monetary policies.

US money supply (M2) grew much faster during the pandemic than during previous quantitative easing implementations. Higher M2 growth may forebode higher inflation but it is already receding. Money supply growth peaked at +27.6% y/y in February and came back down to +13.0% by the end of May.

The Monetary Road Ahead

Anticipating further improvement with economic growth reaccelerating, the Fed is looking to when it should begin reining in its ultra-loose monetary policy. The $120 billion worth of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities the Fed is buying every month has contributed to excess liquidity in the financial system. Tangible signs of excess liquidity at present include: high valuations of stocks, the aforementioned negative real bond yields, the lowest yield spreads on corporate bonds since 2007,[4] average home prices increasing 14.6% over the past year,[5] a heavy Initial Public Offering (IPO) calendar, the proliferation of Special Purpose Acquisition Corporations (SPACs), the return of day traders, meme stocks, cryptocurrency trading, and the rise of non-fungible tokens (NFTs).

Dallas Federal Reserve Bank President Robert Kaplan, one of the more hawkish Fed officials, recently had this to say on the matter: “One of the things that comes with these extraordinary monetary-policy actions is the positive effect on financial assets. It’s also the reason why, as you emerge from the crisis, you want to wean off these extraordinary actions sooner than later.”[6]

Notwithstanding the COVID-19-related market dive and recovery, the retraction of both fiscal and monetary stimulus over the next few years increases the likelihood that markets will become more volatile. In the past, tightening monetary policy, or even reversing loose policy, has been a high-wire act. While the Fed was eventually able to end its QE programs and raise the federal funds rate after the Great Financial Crisis, it wasn’t able to do so without creating some market turbulence. The Fed’s second and third QE programs in 2010 and 2012 were initiated in part because the expiration of the prior QE programs led to stock market softness. In June 2013, then-Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke suggested that the Fed would taper its third round of QE in what has since been referred to as the market’s “taper tantrum.” The S&P 500 fell 4.8% and the 10-year US Treasury yield jumped from 2.18% to 2.54% over the ensuing days. Bond investors accepted the Fed’s thesis that the economy was strengthening, warranting higher long-term rates.

The Fed began raising the federal funds rate under Chair Janet Yellen in December 2015. Although the first rate hike in nine years was well telegraphed, the Fed also provided guidance in December that it expected to raise rates four times during 2016.[7] The S&P 500 fell 9.2% over the ensuing two months. This time bond investors also took a skeptical view, interpreting the Fed’s tightening as bearish for the economy, and driving the yield on the 10-year US Treasury down from 2.22% to 1.66 percent.

The Fed started Quantitative Tightening under Chair Yellen in October 2017 letting $10 billion dollars’ worth of bonds on the Fed’s balance sheet mature each month without replacing them. The plan, implemented as chairmanship transitioned to current Chairman Jerome Powell, gradually increased the maturing amount to $50 billion a month. By the fourth quarter of 2018, topped off with a quarter-point interest rate hike in December, the stock market had had enough of the tightening, tumbling 13.5 percent. The bond market concurred that the Fed’s plan was overly aggressive, with the 10-year US Treasury yield falling from 3.05% to 2.68% in the fourth quarter and starting a much longer drop. The Fed relented, stopping its rate increases and its program of letting bonds roll off its balance sheet.

Through past interest rate cycles, fear of inflation has motivated the Fed to raise rates. At least since 2000, inflation has not been as much of a problem for the stock market as the Fed’s anticipatory tightening actions have been. The Fed has continuously learned to take a more measured approach to tightening, and is learning to communicate better their intended adjustments well in advance. They further seem to have learned that greater tolerance for inflation could lead to more stable monetary policy. After each of these not-well-coordinated attempts to tighten monetary policy, the stock market of course moved on to new highs, offering examples of why we generally recommend investors stay invested.

A Mid-Course Correction

Confident that it can maintain stable price levels, the Fed had pivoted to focus more on its other mandate, maximizing long-term employment. The Fed is still looking for the economy to recover a further 6.8 million jobs lost during the pandemic. Most economists believe that looser monetary policy – “letting the economy run hot” — will help stimulate the economy and employment. Since the Fed had shifted the emphasis of its policy objectives however, it has been unclear how the current Fed would prioritize its potentially competing mandates.

In June, the Fed made a course adjustment. With inflation statistics coming in higher than they expected for April and May, Fed officials wanted to communicate that they remain attentive to their inflation-fighting mandate. The Fed released guidance suggesting they might increase interest rates twice in 2023 – that’s earlier than what Fed officials had previously communicated and earlier than most observers had been thinking. Bond yields fell on the realization that the Fed would be more willing to sacrifice economic growth in order to maintain price stability than previously believed. Starting the year at 0.92%, the 10-year US Treasury yield rose to 1.75% in the first quarter, before falling back to 1.44% through mid-year despite the high inflation statistics being reported. The course correction succeeded in reminding investors that at least some Fed governors intend to prioritize fighting inflation.

Staying Invested

Supply shortages will extend economic growth, while the reopening of other nations’ economies will keep upward pressure on both global demand and prices. At the same time, the satiation of pent-up demand and the exhaustion of fiscal stimulus are reasons US economic growth will slow from its current high pace. As economic growth slows, inflationary pressures are likely to come off the boil. We expect US real economic growth and inflation are likely to be elevated for the next two years, gradually decelerating, with GDP growth settling back to around 2.0% and inflation settling into a range of 2.0%-2.5% beyond that. These expectations are generally in line with the Fed’s own forecast for longer-run real GDP growth of 1.8%-2.0% and modestly higher than its forecast for Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) inflation of 2.0 percent.[8]

The reduction of both fiscal and monetary stimuli probably also means we are entering a period of greater volatility for markets. Two years is a long time for stock traders, typically an excitable bunch, to remain equanimous. The markets will undoubtedly present surprises along the way. In managing the withdrawal of monetary stimulus, the Fed may cause some market turbulence, and will adjust its plans as circumstances evolve.

Our expectations for a return to modest growth suggest longer-term interest rates will also stay fairly low. Stock investors are familiar with this environment, and it has been favorable for stocks. Stock valuations may stay at elevated levels.

Larger disappointments along the path to stable growth would likely prompt further fiscal and monetary support. The general popularity of the fiscal measures taken during the pandemic assures that they will be used with comparable verve during the next crisis. While economic shortfalls may be inherently deflationary, we know how the Fed responds – they add reserves to the banking system. The government’s more active role may induce somewhat greater long-term inflation. As we’ve just experienced recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic, these episodes can still offer particularly rewarding opportunities for investors. However the outcome unfolds, investors will likely be rewarded for their patience. We believe staying invested in high-quality stocks is the best way to grow wealth over the long term.

Adrian G. Davies, President