What will 2021 bring? Two thousand twenty was a crazy year, and the S&P 500 Index returned 18.4%, having appreciated 31.5% in the prior year. The equity benchmark’s strong 2020 performance included the rapid, steep bear market brought about by COVID-19, followed by an equally dramatic recovery. The market started reaching new highs again by August and continued to reach new highs through year-end. If the pandemic can’t cause more lasting damage to stock prices, can anything?

A survey of economists finds they expect the US economy to grow 4.0% this year, after having fallen 3.5% last year.[1] As vaccines for COVID-19 are rolled out, pent-up demand for dining out, travel, and entertainment will be unleashed. Business for hotels, airlines, restaurants, sporting events, and live entertainment will accelerate into the second half of 2021, with the surge in demand driving up prices. The economy will be bolstered both by the well-to-do being able to spend again, and by the underemployed getting back to work. Some consumer spending for these services is likely to shift out of home improvement projects, furniture, and electronic devices, all of which boomed during the pandemic. There will be some more lasting changes to work protocols, but we expect most office workers will go back to working in their offices most of the time. The economy will be further boosted by the $900 billion stimulus bill passed in December 2020, if not a larger fiscal stimulus package supported by the new Biden administration.

While these tailwinds look set to be the dominant economic drivers in 2021, there will be some offsetting headwinds. Many small businesses have folded for good. A backlog of evictions and foreclosures will be a drag on the economic recovery, and student loan payment moratoriums are due to end. If only because last year’s prices were heavily deflated during the downturn, inflation statistics seem poised to rise at least temporarily.

Determined Monetary Action

The stock market has rallied in anticipation of a robust recovery, but this narrative does not explain why the S&P 500 Index is trading at relatively high price-to-earnings multiples against mostly recovered 2021 and 2022 earnings expectations – 22.6x and 19.3x respectively[2] – nor does it explain why bonds are also trading at such a high level relative to their history. High prices mean low yields. Bond prices typically trade higher when the economy is expected to enter a recession. Over the course of 2020, the 10-year US Treasury yield fell from 1.92% to 0.92%, after bottoming once in March at 0.50%, and a second time in August at 0.51 percent.[3]

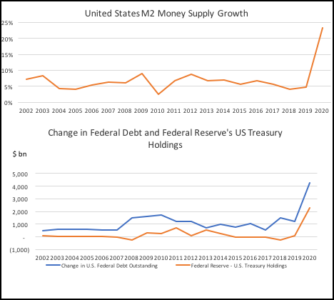

We maintain that central banks’ monetary actions have been a principal force driving both stock and bond prices higher around the globe. The US Federal Reserve continues to buy $120 billion worth of bonds every month, paying for these bonds by crediting commercials banks with newly created reserves. When the commercial banks lend against these new reserves, the money supply expands. The US money supply (M2) has expanded by 7.5% per year since 2007, and was up 24.4% last year. Commercial banks were not in a position to make new loans in the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis, muting the monetary effects of the Fed’s bond purchases. The recession itself was a powerful deflationary force, further offsetting any inflationary implications of monetary expansion at the time. The world’s other major central banks engaged in similar bond buying programs, with comparable results. Whatever deflationary forces have offset the Fed’s monetary accommodation, there has not been significant price inflation since the Great Recession.

It is still too soon to know if last year’s 24.4% money supply expansion will cause more lasting inflation. Inflation hasn’t been a problem for forty years, but money supply hasn’t grown more than 13% in any of those years, either. Federal Reserve governors are likely to overlook a near-term rise in inflation, dismissing it as temporary. Furthermore, with inflation having chronically missed the Fed’s expectations for most of the past ten years, the Fed governors want inflation higher. They recently revised their inflation targeting policy to say that inflation should average 2% over time. The Fed is more willing to tolerate inflation above its targeted level of 2% to compensate for the time inflation has spent below the target. We could see the Fed now tolerating inflation up to 3% or maybe higher on a short-term basis. The subtle revision to Fed policy should reassure investors, because expensive stocks and tightening monetary policy have historically not been a good combination for stock prices.

A Growing Willingness to Spend

The Fed’s bond buying has driven asset prices higher, helping individuals who own assets, but also contributing to wealth disparity. Fiscal spending is mostly intended to narrow wealth disparity. Persistently moderate inflation has also tempted politicians to support higher levels of deficit spending. In 2009, the US government enacted the $800 billion American Recovery & Reinvestment Act to address the Great Financial Crisis. By contrast, in the first half of 2020, the government approved four bills, including the CARES Act, appropriating $2.7 trillion to address the pandemic and associated economic downturn.[4] Importantly, politicians became more comfortable running greater fiscal deficits even during the broad economic expansion from 2009-2019. The federal government’s operating budget deficit was almost $1 trillion in fiscal 2019 alone, amounting to 4.6% of GDP, after 10 years of steady economic growth,[5] before burgeoning to $3.1 trillion, or 14.9% of GDP, in the fiscal year through September 2020.[6] In the wake of the Great Financial Crisis, and then again in 2020, it has also been the case that the Federal Reserve has been effectively buying much of the new federal debt created. Changes in US federal debt outstanding and changes in US Treasurys held on the Fed’s balance sheet are presented in Figure 1. Prior generations of economists and politicians would have blanched at the thoughts both of racking up so much debt during peacetime and also creating new money to pay for such spending, for fear of creating inflation. Despite the high levels of spending and monetary expansion, inflation has so far remained quiescent.

Figure 1

Sources: St. Louis Federal Reserve FRED, FederalReserve.gov

Fiscal spending serves to support the economy, but we seem destined to test the limits of what’s possible, if we haven’t already. We risk creating too much money and spending too much, eroding confidence in the financial system and the currency. The counterargument is that as long as the economy remains healthy, as long as companies continue to innovate, and as long as people have a vested interest, they will continue to have faith in the financial system and the currency. Inflation does a lot of things, most of them not good. However, one benefit of inflation is that it makes the debt burden more manageable for future generations.

Implications for Stocks

The economy enters 2021 with unused productive capacity, and with our monetary and fiscal levers at full throttle. These should all drive strong growth. Although the overall stock market is trading at a historically high valuation, individual stocks are trading with a wide dispersion of valuations and growth profiles. We believe the market of stocks still offers attractive investment opportunities amidst some overpriced stocks. Maintaining diversified portfolios and being ever mindful of tax consequences are key tenets of Woodstock’s investment philosophy. Then, with well-earned humility in our ability to forecast the economy and the stock market, we will do our best to position investors’ portfolios for the outlook we see ahead.

Adrian G. Davies, CFA, President