Woodstock Quarterly Newsletter / Summer 2018

The S&P 500 Index returned 2.65% through mid-year, recovering from its modest loss in the first quarter and remaining below its January high. Large capitalization internet and technology shares continued to dominate performance, with Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Microsoft, and Netflix accounting for 99% of the S&P’s modest gain.[1] Seven of the S&P 500’s current eleven sector classifications were down through mid-year.

The broader returns are modest considering S&P 500 Index earnings are expected to be up 20% this year, boosted by the corporate tax cut, and then up 10% next year.[2]

The US economy remains healthy, having grown at a 2.2% rate in the first quarter and forecast to grow 2.9% for the full year.[3] The nine year economic expansion is the second longest in US history.[4] The relatively vibrant economy and accelerating inflation drove the yield on the 10-year US Treasury up from 2.43% at the beginning of the year to 2.85% by mid-year. Bond yields and interest rates move inversely with bond prices. In May, the 10-year Treasury yield peaked at 3.10%. While the 10-year US Treasury yield rose, short term interest rates rose even faster. The Federal Reserve has raised the Fed Funds rate twice this year, from 1.42% at the beginning of the year to 1.91% by the end of June. Fed officials aspire to raise rates to a level which neither stimulates nor impedes economic growth, and for the most part feel that we aren’t there yet.

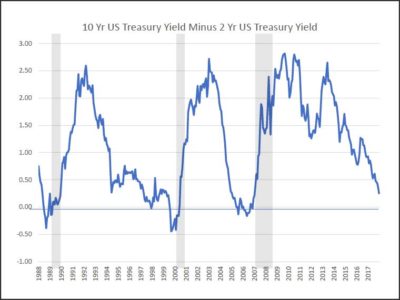

Many investors look at the difference between the 10-year US Treasury yield and the 2-year Treasury yield as a gauge reflecting the longer term prospects for the economy. A bigger differential, referred to as a steeper yield curve, suggests investors expect strong economic growth and/or inflation. The yield curve has been flattening of late, to the point where the difference between the 10-year Treasury rate and the 2-year rate has narrowed to 0.33 percentage points. Two more 0.25 percentage point hikes would invert the yield curve – making the 2-year yield higher than the 10-year yield – if long term rates don’t move higher. Inversion means the market believes short term interest rates will fall, as typically happens during recessions. The 2s-10s spread has gone negative before each of the past seven recessions.[5] The signal provides an early warning, which can come anywhere from a few months to two years before a recession typically starts. It’s possible that yield curve inversion causes recession: banks tend to finance themselves with short term capital and lend money on a longer term basis. If banks can’t lend profitably, they will scale back their lending. The ensuing credit contraction can cause a recession.

As an economic indicator, the yield curve clearly contrasts with most other economic statistics. Most economic statistics suggest the economy is doing better than good: gross domestic product (GDP) growth, unemployment, durable goods orders, etc. have all been fairly robust. The unemployment rate is close to all-time lows. Inflation seems to be finally turning up. The economy is digesting not only a stimulative corporate tax cut, but considerable fiscal expansion. According to the Congressional Budget Office’s baseline estimates, federal deficits will average $1.2 trillion per year through 2028.

The deficit is projected to increase from 3.5 percent of GDP in 2017 to 5.4 percent in 2022. Rather than slowing down, the economy could just as well overheat, but that’s not the message the 10-year Treasury yield is conveying.

It is generally understood that the Federal Reserve controls the short end of the yield curve through its open market operations. The long end of the curve is generally deemed to be set by market forces. Would the Fed deliberately set the Federal Funds rate higher than the 10-year Treasury rate? If the Fed were to raise the Fed Funds rate above the 10-year Treasury rate, and the economy were to subsequently fall into recession, that’s probably not something any Fed Governor would want to have on their resume. Fed Governors James Bullard, Neel Kashkari, Raphael Bostic, and Patrick Harker have said they would be reluctant to raise the Federal Funds rate above the 10-year Treasury rate.[6] And yet the consensus of Fed Governors is that there will be two more rate hikes this year and three more next.[7] Clearly, many Governors are counting on the 10-year Treasury rate rising from its current level.

A number of factors may be working in concert to keep long term interest rates low, with the monetary policies of other central banks being an important one. The European Central Bank (ECB) is still buying €30 billion of bonds per month and the Bank of Japan (BOJ) is still buying ¥270 billion per month to stimulate their economies. These monetary actions have helped drive yields to 0.301% and 0.031% respectively for German and Japanese 10-year government bonds. US Treasury yields remain attractive relative to these major currency counterparts, but are probably still trading lower than they would be if other central banks weren’t as aggressively managing their yield curves.

Another dynamic which could explain low long term yields is the relative supply of and demand for Treasury bonds. Low interest rates indicate that demand for long term Treasurys is fairly strong. As has been the case for some time, most of the Federal Government’s outstanding debt consists of short maturity issues. The Treasury Department is responsible for deciding what proportion of the Government’s debt to finance in short maturity paper versus long term debt. The Treasury could shift the relative supply of available maturities among its debt issues.

Similarly, the Federal Reserve currently manages a $4.2 trillion portfolio of bonds, so their decisions about whether to buy short term or long-term paper also influences the demand and supply of US Treasury debt at different maturities. Buying only short duration bonds would be the reverse of Operation Twist, whereby the Fed swapped short maturity bonds for long term bonds in 2011-2012 for the express purpose of bringing down long term rates. But the Fed’s primary consideration may not be managing the 2s-10s spread – they may be more focused on keeping mortgage rates and other long term borrowing rates low to stimulate growth.

The trade war could be further depressing interest rates as investors fear economic disruption and flock to safe-haven securities. The trade war is supposed to be resolved in the near term — it should not have much effect on a long duration asset. Then again, the trade war probably shouldn’t affect foreign exchange rates either, and it has been.

On the other hand, market forces may drive long term interest rates back up. Rates remain low relative to nominal GDP growth. Rising Federal deficits are one factor that ought to increase the supply of Treasurys. The ECB is expected to taper its bond buying program by the end of the year. And low US unemployment should drive wage inflation, which should drive inflation higher more broadly. We expect inflation to rise at least in the near term.

Rising long term interest rates could potentially have a worse impact on economic growth than yield curve inversion. Interest rates usually rise because either economic growth or inflationary pressures are accelerating. The danger would be if interest rates were to rise not because of economic strength or inflation, but because central banks are withdrawing their policy accommodation. Higher interest rates would then slow economic growth, with slower economic growth eventually driving rates back down.

Yet another interpretation of the current low rate environment is that the Fed’s tightening activities themselves are keeping long term rates low. Despite the Fed’s goal of seeking a neutral interest rate, the Fed’s monetary tightening may serve to constrain both economic growth and inflation expectations. Perhaps the market is trying to tell the Fed their rate hikes will keep economic growth modest. Economic growth and inflation might be higher over a ten year period if the Fed were to stop raising rates presently.

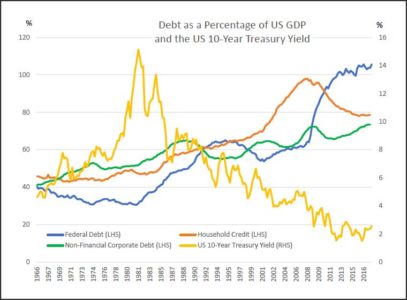

The conventional thinking is that rates should normalize, and that normalized rates are somewhere north of where they stand today. GDP growth is approaching historical levels and interest rates should be too. The Fed has expressed some interest in having some “dry powder,” meaning they want to raise rates now so they can lower them during the next economic downturn. But normalized interest rates might be structurally lower than where they’ve been in the past. Our collective debt levels (government, corporate, and consumer) have been expanding for forty years, and interest rates have been in a downtrend for forty years. Our debt levels may be limiting our economic growth potential. At higher debt levels, economic growth is more sensitive to changes in interest rates. If interest rates are appropriate for the total amounts of debt currently outstanding, the 2s-10s spread indicator may be correctly suggesting the likelihood of a recession has increased and additional rate hikes might precipitate one.

The Fed should further be mindful of the impact higher US rates would have on foreign economies, currency exchange rates, and trade conditions. Interest rates around the world might either be pulled up in sympathy with US rates, dampening global growth, or the US Dollar might rise further than it already has, limiting our ability to export. President Trump has a point when he argues the Fed is counteracting much of what he intends to accomplish with trade policy. The Fed probably should at least slow the pace at which it is raising rates.

Limiting our fiscal deficits would require short term sacrifice in order to restore economic vibrancy over the longer term. If it’s unrealistic to expect our elected officials to instill fiscal discipline, then our eventual fate could be more dollar printing. That wouldn’t necessarily happen even in the intermediate future, and, if it were to happen by the way, we would still recommend staying invested in stocks versus bonds or cash.

Trade War

The trade war has so far had minimal effects on the US economy, but it is having some effects on markets. The US Dollar rose about 3%, and emerging markets stocks fell 7% year-to-date through June. The Shanghai Stock Exchange Composite Index fell 8.4% in June. A number of emerging market currencies also fell. The Chinese Renminbi fell 3.4% in June. The trade war has made some commodity prices rise (steel, where we are imposing import tariffs), and others fall (if they will be subject to other countries’ tariffs). Soybeans fell 16% in June. Although tariffs were not imposed on copper, copper prices fell 3% in June and have continued to fall as concerns about global trade have increased.

Newly imposed tariffs are intended as a negotiating tactic and should be temporary. As long term investors, we are looking beyond the trade war. As of this writing US stocks also appear to be looking beyond it and the potential damage tariffs may cause in the short term. The longer the bravado and posturing continue publicly, however, the more the tariffs will dampen economic activity, while we can’t know what trade negotiations are going on in official circles behind the scenes. There could be some inflationary and some deflationary implications of the trade war over the next year or so. Overall, we don’t expect the Fed to do much in response, although they could defer an interest rate hike to offset the new uncertainty. Another concern is that businesses sought to stockpile key inventory ahead of the potential trade war. Such ordering would not have been enough to have lifted GDP significantly, but may have been enough to send misleading signals about growth rates. We’ll know soon enough if growth rates subside.

We hope the Trump Administration is successful in persuading our trade partners to open their markets further to US trade and investment, and in securing greater protections for US intellectual property rights. We also need to consider the possibility that trade patterns shift as a result of the tough-handed tactics in ways that aren’t advantageous to the US over the long term. After US withdrawal, Japan took the lead on TPP negotiations, and now Japan is working out trade terms with the European Union.

Tariffs imposed to date will have a much bigger effect on the Chinese economy than on the US economy, considering exports account for 20% of China’s GDP and only 12% of the US’s. Unfortunately however, we are engaging in trade wars with all of our major trading partners at the same time. Furthermore, we are operating against an implicit deadline, the US mid-term elections.

The Trump Administration would like to see trade negotiations neatly wrapped up in time to bring a victory home to its electoral base. While we would like to see the aggressive trade negotiations wrapped up quickly, we would be disappointed to see our negotiating position compromised by an artificial deadline.

We are pleased to report that the environment has been quite favorable for stocks. According to FactSet consensus estimates, the S&P 500 Index finished the quarter trading at 16.9x 2018 earnings and 15.4x 2019 earnings. Economic and earnings growth will most likely moderate, but the market’s valuation seems to account for this. Although the trade war presents a possible near-term challenge for stocks, we believe investors would welcome a favorable resolution and stocks will come out of the trade war in good shape. While tightening monetary conditions and rising interest rates present potentially bigger challenges to the markets, we don’t see the Fed deliberately inverting the 2s – 10s Treasury spread. Any let-up in the pace of monetary tightening would probably be well received by the markets. We remain focused on investing for the long term, but we are happy to incorporate nearer term client needs into portfolio positioning as necessary. Please contact your portfolio manager if you have questions.

Adrian G. Davies is Executive Vice President at Woodstock Corporation. You may contact him at adavies@woodstockcorp.com.

[1] Vlastelica, Ryan, “Stock gains in 2018 aren’t just a tech story, but they’re mostly a tech story,” Marketwatch.com, 7/12/18.

[2] FactSet

[3] Bloomberg consensus estimate, 7/14/18.

[4] Ploutos, “Length of Economic Expansions,” Seeking Alpha, 7/6/18

[5] Duy, Tim, “Flat Yield Curve May Result in a More Aggressive Fed,” Bloomberg, 6/8/18

[6] Smialek, Jeanna, “Kashkari Isn’t Buying ‘This Time Is Different’ for Yield Curve,” Bloomberg, 7/16/18

[7] US Federal Reserve Statement of Economic Projections, June 2018