The S&P 500 Index dipped briefly into correction territory in mid-March (defined as at least a 10% fall from a recent stock market peak, which it hit January 3rd) before rebounding to close out the first quarter down only -4.95% as of March 31st. The tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite Index was off -9.1% on a price-only return basis for the quarter, but technically has been in correction territory since mid-January, down -11.4% from the highs it hit November 19th. Likewise, bonds had a tough quarter, finishing in the red with long-term Treasurys down -10.2%. Energy and utilities were the only equity sectors with positive price returns, +37.7% and +3.9%, respectively. All of these markets were digesting news of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, high energy prices, surging inflation, and a Federal Reserve turned hawkish with forecast aggressive federal funds rate hikes and open market bond sales to shrink its balance sheet. The question everyone is asking: Can the Fed orchestrate a soft landing with so many variables to combat? Not likely.

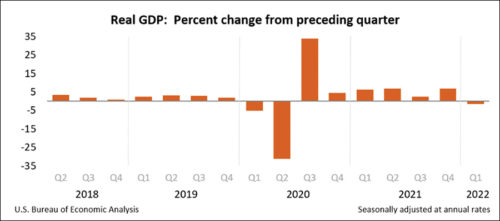

The Federal Reserve and Federal Open Market Committee will attempt to engineer a soft economic landing (rein in inflation without hurting employment) and avoid sparking a recession with the few tools at its disposal. Recession is marked by two consecutive quarters of negative real GDP growth. Advanced estimates by the Bureau of Economic Analysis indicate real GDP decreased at an annual rate of -1.4% in Q1, compared to an increase of 6.9% in Q4 (see Figure 1). The decline was driven in part by decreases in net exports (imports exceeded exports, which negatively impacted GDP), government spending, and inventory investment which more than offset the rise in personal consumption. The real GDP decline could be seen as a brief and modest GDP hiccup that will abate as supply chain bottlenecks ease. It could also be a canary in the coal mine, signaling danger ahead.

Figure 1. Real GDP

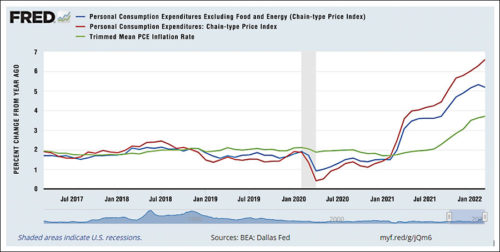

The inflation rate was 8.5% in March 2022 as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), the highest in 40 years (since December 1981), up from 7.9% in February. Energy prices were up 32%, driven by fuel oil (+70.1%) and gasoline (+48%). Food prices were up 8.8%, used cars and trucks were up 35.3%, and new vehicles were up 12.5 percent. Core CPI, excluding energy and food, was up 6.5 percent. The Fed focuses on personal consumer expenditures (PCE) to measure inflation, considering it the most reliable statistic. PCE rose a more muted 6.4% in February, and core PCE, also excluding energy and food, rose 5.4% (see Figure 2). The expectation of higher future prices tends to increase demand in the short term, pulling forward purchases and sustaining the inflationary cycle.

Figure 2. Inflation as Measured by Personal Consumption Expenditures

Supply Issues May Foil the Fed In the face of this spiking inflation, there are a number of supply-related factors the Fed cannot control. These include persistent supply chain bottlenecks, lingering pandemic-related supply and labor shortages, war in Ukraine, and energy, food and commodity inflation among them. So, the Fed must focus on the demand side of the equation. It has changed its tune from repeated reassurances in the fall that inflation will be transitory to a very hawkish stance. The Fed executes their stated goals of promoting maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates primarily by manipulating the federal funds rate and through open market purchases and sales of Treasurys, agency bonds, and mortgage-backed securities. They, and we, hope these tools will be used correctly to cool an overheating economy, slowing growth but not eliminating it. Ideally their tightening policy will reduce personal consumption, reduce investment, stimulate slower but still positive GDP growth, and thereby lower inflation back toward its long run goal of 2 percent.

The Fed may eventually be successful, but it will more than likely take longer than they expect, and also likely cause at least a mild recession. Historically, 11 of the 14 Fed tightening cycles since World War II have resulted in a US recession within two years.[1] This ominous track record aside, actions they take today and in the coming year will have a lagged impact on the economy, and many supply-side variables beyond their control will have unknown intervening consequences affecting the probability of a “soft landing.”

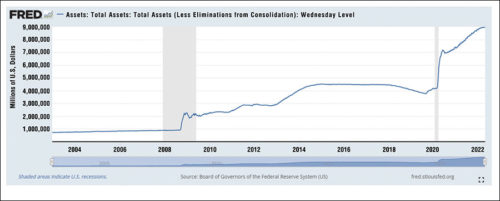

The Fed balance sheet has doubled in the pandemic crisis to $9 trillion (see Figure 3). The Fed announced it is beginning to unwind the run-up by letting $95B of Treasurys, agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities mature without reinvestment per month. It is not yet known how long the Fed will let this balance sheet runoff continue; however, at that rate it would take nearly four years to bring the balance sheet back to pre-pandemic levels. The effect is to take liquidity out of the banking system, making lending more expensive. In March they also raised their federal funds rate target from 0.0%–0.25% to 0.25%–0.5% (by 25 basis points). They raised rates an additional, and more aggressive, 50 basis points in May.

In the 1970s and early ‘80s, the Fed raised target rates to a level that exceeded the rate of inflation in order to bring high inflation back under control. The federal funds rate peaked at 20% in 1980. With inflation in March 2022 spiking up to 8.5%, a similar path of very high prescriptive interest rate hikes would cause chaos in the financial markets here and abroad. The Fed cannot raise rates that high or that quickly now without destabilizing the global economy. It should raise rates at a measured and steady pace. Economists are predicting 5–6 more rate increases this year and markets are predicting a 250-basis-point rise in 2022 in total. The most likely scenario is more aggressive federal funds rate moves in the coming months and less aggressive raises in the second half of 2022.

Similar to the open market bond transactions, raising rates will make it more expensive for companies and consumers to borrow. Combined, these two Fed levers should help crimp demand for goods and services by consumers and companies alike, slowing GDP growth, but also impacting employment, housing and market valuations. A decline in the valuations of real estate and financial assets may have the greatest impact on consumer demand, and do so far more quickly than the Fed tightening cycle.

Figure 3. Fed Balance Sheet December 2002 to April 2022

Labor Market Impacts

The labor market is currently in good shape from the Fed’s point of view, so while they will be mindful of unemployment spikes, their focus will be primarily on taming high inflation, which has become a much bigger challenge. The March unemployment rate hit historic lows of 3.6% (decreasing by 318,000 to 6 million people), though this may not fully count those who have left the workforce, cannot work due to the pandemic, are underemployed or working part time out of necessity. US wage growth was up 9.16% as of December 2021, steadily declining monthly from a peak of 15.3% in April 2021. There were roughly 56 unemployed workers for every 100 job openings at the end of February, with 11.3 million job openings and 6.3 million unemployed workers (see Fig. 4).

Statistically, we are essentially at full employment, which creates its own inflationary pressures. Labor shortages, higher minimum wages, and wage inflation to attract and retain workers all contribute to a perpetuating cycle necessitating higher pricing for goods and services that feed inflation. The Fed’s policies designed to slow this economic growth would work counter to full employment goals and would have the effect of raising unemployment, cutting job openings, and limiting wage increases. Rising interest rates, combined with energy and food inflation, will reduce consumer demand. Forgoing discretionary spending, delaying large purchases, and trading down to lower-priced products would have a material impact on economic growth since consumer spending comprises 70% of GDP.

Figure 4. Unemployment Rate vs. Job Openings

Real Estate Valuations

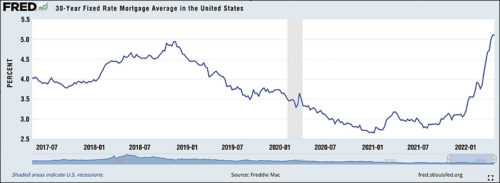

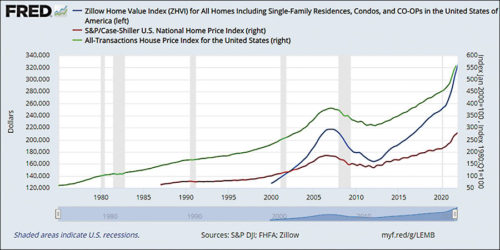

The rise in housing prices in the US has been fueled by historically low mortgage rates, pandemic isolation, and record low supply. With the Fed tightening cycle underway, mortgage rates have quickly jumped, hitting north of 5% for 30-year mortgages after quarter-end, up 64% year-to-date. Mortgage refinancing volume dropped 60% year-over-year in March. The current limited housing inventory will keep prices up in the short term as it will likely take some time for housing demand to come back in line with supply. However, if mortgage rates remain elevated, and continue to rise with the Fed hikes, housing demand will drop along with valuations. (See Figures 5 and 6.)

Figure 5. Mortgage Rates Skyrocket

Figure 6. Home Prices Soar

Energy and Food Inflation

Energy prices are one of the main inflationary factors the Fed cannot contain with its actions. The energy sector had a supply-and-demand imbalance even before Russia invaded Ukraine that was driving energy prices higher. Post invasion, embargoes of Russian oil and gas only add to the supply weakness. Russia supplies 12% of the world’s oil. The prices of oil and natural gas have risen 33% and 51% in the quarter, respectively. The remaining producers cannot replace this supply overnight, having underinvested in the preceding years of low energy prices. An elevated price of oil in the $100-per-barrel range is likely to remain for some time, despite President Biden’s gradual release of 46% of the nation’s strategic petroleum reserve. By extension, energy inflation in the form of higher prices for gasoline, jet fuel, and heating oil, higher costs for electricity, transportation, delivery of raw materials, and production of finished goods will continue to inflate prices across the spectrum of goods and services, despite the Fed’s actions. The Russian-Ukrainian conflict is likely to go on for some time, prolonging the pain.

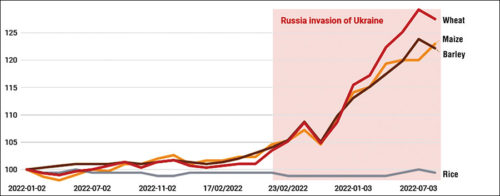

Like oil and gas, food inflation is a problem the Fed can’t solve locally. Russia and the Ukraine are breadbaskets of sorts, supplying grain to many countries, accounting for 25% of the global wheat supply. The current war there has disrupted vital food security supply chains in many developing nations, particularly Egypt, the largest wheat importer, at a cost of $4 billion annually. Wheat prices rose 30.5% in the first quarter. As a result of price hikes, many emerging market nations are now rationing both food and energy, with their governments having to decide between feeding their people and paying their debts.[2] History has shown us that food inflation in countries that have few alternatives has eventually led to geopolitical unrest, defaults, and regime changes. (See Figure 7)

Figure 7. Wheat, Maize, Barley & Rice Price Indexes

100 = Price on February 1, 2022

Source: International Grains Council • Get the Data

The Yield Curve

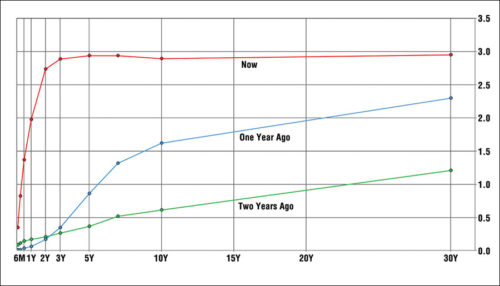

The rise in short-term rates has caused the Treasury yield curve to flatten, beginning at two-year maturities, and briefly to invert with the 2-year Treasury yield temporarily exceeding the 10-year yield. That longer-term rates have yet to rise in lockstep with Fed hikes implies long-term inflation expectations are still moderate, in line with the Fed’s stated long-run goals of 2%, while shorter-term rates appear to have Fed rate hikes baked in. Longer-term rates are expecting the Fed tightening to be successful in cooling down the economy, reining in inflation, pricing in this future economic softening. If the Fed overshoots its objectives and drives the economy into recession, the long end of the curve may be pricing in that outcome too. The current flattening of the Treasury yield curve could see moments of inversion at various maturities if the long-term outlook remains gloomy while the short end gets tightened to fight inflation. Historically, an inverted yield curve is another leading indication of pending recession.

Figure 8. Yield Curve US Treasurys (4/29/2022)

Sources: Tullet Prebon Information, SWX Swiss Exchange

Rising interest rates hurt bond investors, with prices moving inversely with the interest rates. Short-term bond yields have already moved up, and bond prices have fallen, in anticipation of future Fed rate hikes. To the extent that inflation endures, or the Fed hikes rates more than currently expected, bond yields could rise further. For an equivalent change in interest rates, longer-maturity bond prices are more volatile than shorter-maturity bond prices because they discount changes in rates over a longer period of time. In the current context of bond investors anticipating that inflation will moderate, longer-term rates have been more stable than short-term rates, resulting in a relatively flat yield curve. Flat as it currently is, long-term bonds do not offer a sufficient yield premium over short-term bonds to merit assuming the additional duration risk.

Equity Market Valuations

Rising rates should also have the effect of compressing equity market P/E ratios as the discount on future earnings gets greater. With the Fed set on a path of slowing economic growth, and facing a high risk of overshooting that goal, it would appear that earnings expectations will need to come down. The Fed will be actively undermining corporate earnings growth, which is being priced into the market. As a result, current valuations may still be too high. Long-term average market valuations for the S&P 500 Index are 15x-16x price-to-forward earnings, implying current valuations could have more room to come down, particularly for high-multiple growth stocks.

Investor Considerations

Adding it all up, we can expect rising interest rates, more expensive borrowing, slowing corporate investment, slowing corporate earnings growth, contracting consumer spending, persistent energy and food inflation, rising unemployment, ongoing Covid-related supply disruptions, slowly easing supply chain bottlenecks, and repricing of the housing and equity markets. It is hard to envision a scenario where Fed actions coax all of these economic forces to ease into a perfect equilibrium where economic growth is modestly positive, unemployment remains low, and inflation glides back to long-run goals of 2 percent. An economic recession may be on the horizon.

This doesn’t mean it is time to head for the hills. Stock markets price in changing economic expectations quickly and often. Trying to correctly time getting out and back in again is a fool’s errand—nearly impossible to get right. We recommend investors focus on companies benefitting from long-term secular growth, staying invested through market cycles, and taking advantage of market dips to buy these good companies at better prices. The best companies take advantage of the opportunities presented to them, even finding ways to capitalize on stock market and economic weakness. Finally, keeping enough liquidity for known cash needs in any economic environment is always a prudent strategy.

Robert B. Sanders, CFA, Senior Vice President