Socially responsible investing (SRI). Integrating environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors in the investment process. Applying principles for responsible investing (PRI) to investment decisions. Sustainable. Green. Ethical. Impact investing. These terms are all part of the socially conscious investment jargon getting a lot of “airtime” in the news media, particularly in financial circles. The goal for all of these investment styles is essentially the same, to produce a positive investment return and a positive impact on society and the environment. From a collective social conscience that has been expanding over many years, customer demand for ethically constructed investment portfolios has spawned a dramatic growth in the number of mutual funds, exchange traded funds (ETFs), indexes, and investment firms that espouse or adopt some flavor of these ideals. In tandem, the volume of assets under management incorporating these ideas has grown exponentially. Has this segment of the investment ecosystem leapt from burgeoning social trend to reflecting the prevailing values of society as a whole, and what does that mean for investing moving forward?

Background

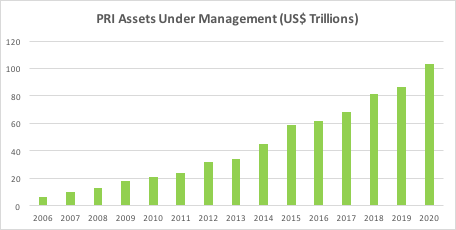

Socially responsible investing is a concept that has been around in modern times for at least fifty years. The global march of social conscience has taken a number of giant steps over the years to bring the world to the level of social awareness we have today. With its beginnings as religion-based ethical and moral judgements eschewing investment in so-called “sin stocks,” SRI initially entailed excluding stocks associated with producing or selling alcohol, tobacco, firearms, and gambling. Abhorrence to owning weapons manufacturers grew during the anti-war movement of the 1960s and 1970s. With the establishment of the US Environmental Protection Agency in 1970, environmental concerns began receiving more attention. The Anti-Apartheid Movement to boycott investments in South Africa gained traction in the US in the 1980s, bringing focus to social issues. Fossil fuel companies came under the gaze of SRI later in the ‘80s, accelerating the environmental scrutiny triggered by the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989 that polluted 1,300 miles of Alaskan coastline. In 2004, the United Nations created a global compact through a joint initiative with financial market participants, resulting in a report titled “Who Cares Wins.” The report introduced the concept of incorporating environmental, social, and governance information (ESG factors) in research, reporting, and investment processes. This report was followed up with the United Nations’ Principles for Responsible Investment in 2006, a list of six principles designed to encourage the adoption of ESG in investment decision making, disclosure, and ownership. Today, over 3,000 investment firms have committed to PRI, representing $103 trillion of assets globally.[1]

Figure 1

Source: United Nations Principles for Responsible Investing, March 31, 2020, unpri.org.

Measurement

With this history and current collective social zeitgeist, it is not surprising that some investors would ask questions about how their assets are managed, why companies are included or excluded from their portfolios, and how these companies have performed, not only financially, but on a societal level. Investment returns are a straightforward calculation. To incorporate relative values of social “good citizenship” in an investment process and associated reporting, companies need to disclose ESG-specific data, and we need a scale of measurement to evaluate performance. A number of ESG rating scales have been proliferated by data companies over the years, including a numeric score (best score =100), and an alphabetic rating similar to Standard & Poor’s bond credit rating (best score = AAA). There is not currently one standard that investors can agree upon, but that doesn’t prevent investors from trying their best to enact the concept with the information they can get.

Each of the three segments of ESG factors will have its own set of value judgements. How these values equate across segments can be very subjective. Environmental factors may include waste, pollution, carbon emissions, and utilization of natural resources. Social factors evaluate how a company treats its work force and interacts with society. This may run the gamut from product safety to labor diversity or human rights in the supply chain. Elements of governance factors may include corporate corruption, or gender and racial diversity among executive ranks and boards of directors. Some industries are more heavily weighted toward one or more of these ESG factors than others. Environmental impact may count more for energy companies, governance may dominate in service firms, and labor relations overshadow manufacturers. Given the diversity of issues in a particular industry, or a single company, one can imagine the difficulty of weighing one factor relative to another. For example, how would one compare a car company with a poor environmental record but good labor relations against a car company with a poor labor record but favorable environmental scores?

Value judgements are very subjective and their relative importance may be different for every investor. Each ESG rating scale attempts to capture the level of complexity embedded in the range of issues and impacts a company may encompass. ESG ratings may well be a good starting point to a socially conscious investment decision. As the saying goes, the devil is in the details, and proper investment due diligence will likely involve more research when making investment judgements based on a set of values, standards, and priorities. This is a challenge for each investor.

Portfolio Construction

Implementing a socially responsible portfolio may take one or more of several approaches. The SRI process has its roots in the exclusion of certain companies from a portfolio, also called “negative screening.” It is sometimes easier to know what you don’t want, and to avoid it, than to evaluate many companies to determine which to include. Over the years, I’ve had individual clients make specific investment requests, including the exclusion of big oil companies after the Exxon Valdez spill, omission of pharmaceutical companies over animal testing, and abandonment of chemical companies because their weed killer was killing bees, among other restrictions. This merely illustrates that everyone has their own priorities. One approach is positive screening, for example, choosing companies with a socially beneficial theme important to the investor, such as clean or renewable energy. One could also use the ESG factor-based data to pick the best-in-class companies within each sector as the first level of due diligence to narrow the field of investment options. We are not suggesting that ESG ratings can be used exclusively in evaluating the investment merits of a particular security, as these companies might have non-ESG-related challenges that the ratings don’t capture, such as intensifying competition or excessive valuations. However, these ratings could provide meaningful information to investment decisions. Finally, an investor could take a passive approach and choose among the ESG or socially responsible investment products like mutual funds and exchange traded funds that track an ESG index. It is conceivable that using some combination of these methods could achieve one’s socially responsible investment goals.

Investment Performance

Investment advisors have a fiduciary obligation to seek the highest return for a level of risk. Excluding companies or sectors based on value judgements appears to run afoul of a fiduciary mindset. Every sector has its day in the sun in a normal investment cycle, so excluding one or more sectors will have consequences for long-term performance. The US Department of Labor tends to agree. In a proposed ruling from June 30, 2020, a retirement plan covered by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) “requires plan fiduciaries to select investments and investment courses of action based solely on financial considerations relevant to the risk-adjusted economic value of a particular investment or investment course of action.”[2]

You could argue that “sin stocks” would likely outperform in an economic downturn, or that energy companies rally when the price of oil is rising. Taking it a step further, companies with the worst social or environmental records would likely be undervalued relative to their more highly rated peers, and with progressive improvement on those scores, could offer potential to attract a larger pool of investors, and thereby generate better investment performance. As a fiduciary, it is not okay to invest in ESG for the sake of making the world a better place. It is, however, okay to consider ESG factors as part of the fundamental research if you believe that these considerations lead to better investment returns.

It is important to acknowledge that the performance of socially responsible investments has come under scrutiny over the years relative to the performance of traditional index benchmarks. If you begin with the investment premise that companies that are doing social and environmental good should garner lower business risk over time, logically these companies should outperform companies that have higher risk from adverse social stewardship. This assumption doesn’t exactly square with the investment concept of higher risk demanding a higher return. In a world where companies’ customers and other stakeholders have varying levels of ESG consciousness, corporate managements also need to be conscientious about their broader ESG impact in order to optimize their company’s growth potential, and to stabilize earnings from ESG-related risks. In this respect, perhaps what ESG investing offers is a higher risk-adjusted return. However, the jury is still out on whether there is an absolute return advantage to ESG investing.

The ESG community has been striving for years to prove their approach has both social and investment merit. During the early 2020 market decline and subsequent advance, the three US ESG indexes in Table 1 succeeded in outperforming the benchmark S&P 500 Index for the year. These ESG indexes appear to be consistently adding value over longer timeframes, as well.[3] At a minimum, this is evidence that favorable ESG factors may provide some downside risk protection in volatile markets. In what has been a growth-driven bull market for the past ten years, there is not enough data here to conclusively prove ESG factors drove these results, but investors in these strategies were rewarded with improved returns over this timeframe.

Conclusion To answer our initial question, based on the growing level of invested assets, the number of investment firms embracing socially conscious strategies, the proliferation of ESG investment options, and growing consumer demand, it appears that socially responsible investing and ESG investment approaches are here to stay. ESG, with its beginnings as a client accommodation for values-driven investment decision making, is now going mainstream. In the not-so-distant future, ESG and socially conscious investing will merely be called “investing.” The consideration of environmental, social and governance factors will be just another aspect of normal investment due diligence, risk assessment, and performance evaluation. As reporting from companies on these ESG factors improves, the transparency and comparability along these metrics will become part and parcel of portfolio performance reporting.

At Woodstock, your investment advisors are fiduciaries. We manage investments for our clients with that duty in mind. By obligation, and in practice, our portfolios are managed and customized according to our clients’ risk tolerance, return expectations, income needs, ESG preferences, and tax, legal, and other considerations. We believe the companies we invest in generally operate in a socially conscientious manner, or are moving in that direction. A majority of the companies we employ in our portfolio construction are represented in ESG-related indexes. This article’s conclusions would suggest that more consideration of ESG factors for the companies we follow will be warranted in the years ahead, along with a thoughtful approach to addressing individual client ESG preferences. To the extent that this article sparks interest or thoughts along the lines of socially conscious investing, we invite you to reach out to your portfolio manager to begin the conversation. As always, we are here to help you achieve your goals.

Robert B. Sanders, SVP, Portfolio Manager