Rising inflation and rising interest rates were the primary reasons the S&P 500 Index returned -18.1% and the iShares Core US Aggregate Bond ETF returned -13.0% for 2022. Fortunately, inflation now seems to be dissipating. Stocks already reflect some of the good news, returning +7.6% in the fourth quarter while bonds returned +1.6% (bond yields fall when bond prices rise). The bull case for 2023 depends largely on whether the Fed “pivots” changing from tightening to easing monetary policy—but in the meantime a recession still looks probable.

Inflation Is Down…

While inflation is still very high, it is on a trajectory lower, diminishing the threat it posed six months ago. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) was up 6.5% year-on-year in December, down from +9.1% y/y at midyear. The core CPI (ex-food and energy) was up 5.7% y/y in December—down just slightly from +5.9% at midyear, supporting the argument that inflation remains a threat. Importantly however, taking the change in the CPI over the last six months and annualizing it, the headline CPI was up just 0.3%, and the core CPI was up 3.7 percent. For comparison, the headline CPI for the first six months of 2022 was up 13.0% annualized, and the core CPI was up 7.7% annualized. Different components of inflation are coming down at different rates. The difference between headline and core over the last six months primarily reflects a -15.1% decline in energy prices (-27.9% annualized). Prices of commodities other than food and energy increased 2.1% y/y in December. Price pressures have transitioned to services, where prices increased 7.0% y/y. More dependent on US labor, services prices may take longer to settle down. Shelter costs increased 7.5% y/y, but spot rental rates are coming down.

Although inflation has proven tricky to forecast, we believe inflation will continue lower for the time being. Pandemic-related drivers of inflation (fiscal stimulus, monetary stimulus, and supply chain issues), the reasons many of us originally thought inflation would be transitory, are finally dissipating, with the retrenchment of inflation confirmed by numerous reports. Commodity prices, often an early indicator of inflation, have softened considerably since last summer. Since monetary policy works with a lag, the fastest monetary tightening at least since World War II should continue to exert downward pressure on prices. Reflecting monetary policy, US money supply (M2) rose 42.7% during the pandemic to a recent peak (a 16.7% annualized rate of expansion), and has been contracting at an annualized rate of 2.8% rate over the last six months.

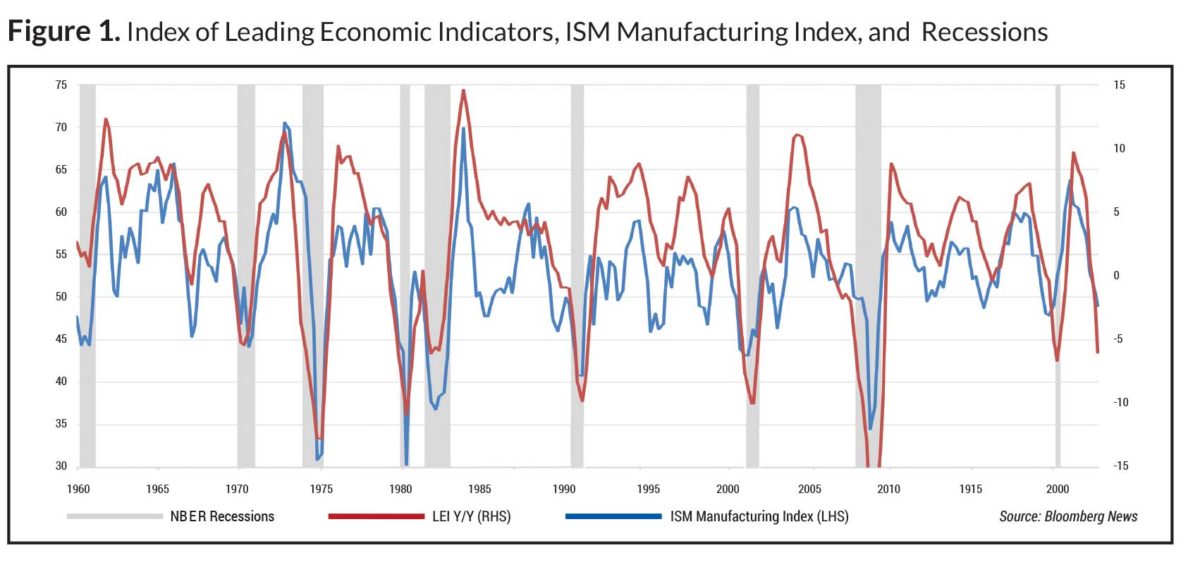

Since inflation and economic growth are correlated, the trajectory of inflation from here will also depend in part on how well the real economy does. Various measures of economic lManagers’ Purchasing Survey (ISM) and the Conference Board’s Index of Leading Economic Indicators (LEI), have entered territories indicative of a recession as can be seen in Figure 1.

…But Not Out

To hazard a guess, inflation seems likely to settle in the 2%-4% range by year-end 2023. This compares to the Fed’s central tendency forecast made in December for 3.2%-3.7% core Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) inflation by year-end 2023. A recession could easily drive inflation lower still, and we expect inflation will be volatile.

Historically, getting inflation down has been difficult. It’s hard to get the proverbial genie back in the bottle. Now that we have gotten somewhat accustomed to the idea of rising prices, it’s harder to stop businesses from continuing to raise prices. The tight labor market, China’s reopening, and the US omnibus spending bill are additional factors which may impede inflation from settling back to 2% in the near term.

Workers left the workforce during the pandemic for a variety of reasons. Unemployment remains at 3.5%, on par with its lowest level in 60 years, and there are more than 10 million job openings. Greater competition in the labor market is driving wages up. Labor disputes are becoming more common. Economists are worried that tight job market conditions will lead to an unhealthy wage-price spiral, whereby workers continue to demand more compensation to pay for the higher costs of living, and businesses continue to raise prices to support higher wages.

China, the world’s second largest economy, has only recently started to open up after a long period of Covid-induced lockdowns. As the country is reopening, it is seeing a re-entry wave of Covid cases which could exacerbate supply chain issues. Some supply chain issues were caused by China’s rigid lockdown policies, so some constraints will be improved while new ones could emerge. More significantly, China’s reopening could drive a fresh wave of pent-up demand, contributing to higher commodity prices and a resurgence of inflationary pressures worldwide.

The strength of Europe’s economy will be another swing factor in the state of global inflation. We have been expecting Europe to be in a recession due to its energy crisis and rising interest rates. While a recession in Europe still seems likely, the winter so far has been moderate, reducing fears the continent will be constrained by high energy prices. China’s reacceleration could offset weakening demand in the US and Europe.

The omnibus spending bill passed at the end of 2022 could be another reason inflation might not go quietly into the night. Given the fiscal spending bender we’ve just been through, it’s hard to see the omnibus spending bill boosting inflation, but by keeping the fiscal deficit high, the $1.7 trillion spending package might keep inflation higher than it would otherwise be.

More fundamental economic forces may be at work as well, driving inflation higher over the longer term. First, we have yet to figure out the extent to which the labor shortage is temporary versus structural. Insofar as it is caused by demographic changes including baby boomers retiring, the labor market could take longer to come back into balance. The labor shortage could last through a recessionary environment or re-emerge during a recovery. Second, having been through a long period of increasing globalization, the world seems to be entering a period of de-globalization. Globalization has been a deflationary force as we have benefitted from cheaper production costs overseas. Now countries and companies are seeking greater security over their strategic resources and capabilities. De-globalization, or “on-shoring,” may be stimulative to economic growth here, but the trend may push production costs higher.

Third, the “greening” of our energy infrastructure and adapting to changing global weather patterns will be expensive endeavors, driving overall costs higher. Finally, if we remain trapped in continual boom-bust cycles, monetary policy itself becomes a source of inflation. The Fed has been over-steering the economy, flooding it with money when the economy is weak. As a result, the money supply goes through fits of expanding by more than the economy can readily absorb.

Should We Expect a Recession?

Higher interest rates have helped bring inflation back under control, but they are transitioning from stronger to weaker. On its way back from “too hot,” the dial would show “just right,” even if it were moving to “too cold.” The economic outlook appears well balanced right now. The dial could stabilize somewhere above zero or, more probably, it could dip to a “colder” reading.

The Fed aspires to tighten policy just enough to slow inflationary pressures without tipping the economy into a recession, but it has had very limited success managing a “soft landing” in the past. Because interest rates affect the economy with a lag of a year or so, the Fed needs to anticipate how interest rate changes over the past year, as well as other economic factors, will continue to unfold. The cumulative effect of higher rates continues to dampen economic growth, while consumers are spending down accumulated savings. US real economic growth had been averaging 2.3% in the years prior to Covid, when interest rates were supportive. The Fed may have already raised interest rates enough to push the economy into a recession, only to be confirmed as new economic reports come in.

Economists have a range of opinions regarding the strength of the economic headwinds we’ll be facing, as well as when they will hit. Some believe we are already in a recession as suggested by the Conference Board’s Index of Leading Economic Indicators (LEI) and the Institute of Supply Management’s (ISM’s) Manufacturing survey (see Figure 1 above), while others believe that given the underlying strength in the labor market, the US won’t enter a recession until 2024. The LEI and ISM could be sending early or false signals. The omnibus spending bill and a number of government programs which adjust for inflation may provide just enough stimulus to keep the US out of recession for a quarter or two. These government programs include Social Security (payments from which increased 8.7% in January), government worker pay scale adjustments, adjusted tax brackets, and minimum wage increases in some states.[1]

Will the Fed Cut Interest Rates?

In the 1980s and 1990s, the Fed struggled to keep inflation down.[2] The federal funds rate stayed a few percentage points above the rate of inflation for almost the entirety of that 20-year period. Due to the economic weakness precipitated by the Great Financial Crisis (GFC, 2008-2009) and its aftermath, the Fed struggled to stimulate growth and get inflation up to 2 percent. The federal funds rate generally stayed below the CPI, resulting in negative real interest rates. Now that we have experienced runaway inflation, possibly with structural elements, Fed officials may once again be challenged to keep inflation down to their target of 2%, necessitating maintaining rates safely above the CPI.

The Fed has made good progress bringing inflation back under control. It is particularly encouraging that inflation is subsiding without a pickup in unemployment, suggesting the Fed can achieve a soft landing. If inflation continues on the trajectory it has been on for the past six months, the year-over-year readings will come down substantially. Continued evidence that inflation is moderating might at some point allow the Fed to cut interest rates. The Fed’s current stance on interest rates would seem out of step with the inflation reports. If people feel that the Fed has conquered inflation, there would be political pressure to ease, and Fed officials might decide to do so. But a few months of CPI readings in the 2%-3% range might not be enough to thoroughly expunge the longer-term threat. The Fed is particularly worried that the tight labor market will continue to pressure overall price levels, and probably wants to see signs the market is weakening before it relents on interest rates. If Fed officials are intent on rebalancing the job market, the market’s current strength suggests they have more work to do tightening. They are likely to leave rates higher for longer, until they achieve their objective of weakening job demand.

Seeing a fall-off in economic activity would certainly provide additional justification to cut rates, even if inflation had not yet reached 2%. Since World War II, the Fed has always cut interest rates when there’s been a recession. Although a recession would force inflation lower still, recessions are followed by rebounds, and officials are concerned that the rebound would rekindle inflation. In the 1980s, then-Fed Chairman Paul Volker raised rates to stem inflation (September 1979 – April 1980). After putting the economy into a recession, his Federal Reserve cut rates. The economy rebounded, but inflation rebounded along with it. Volker was then forced to raise rates even higher (August 1980 – January 1981), creating a longer recession in order to deal inflation a decisive blow.

Having raised the federal funds rate 0.50 percentage points to 4.25%-4.50% in December, current Fed officials indicated their expectation to raise rates another 0.75 percentage points during 2023 at their December Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting. Since September, the Fed has also been allowing up to $95 billion of bonds to mature off its balance sheet every month (quantitative tightening), further tightening financial conditions. Officials were predicting unemployment to hit 4.4% – 4.7% by the end of this year, up from 3.7% at the time, acknowledging their policies will induce some pain and suggesting they are willing to incur it.

If Fed officials succeed in bringing down inflation without causing a recession, they would have no reason to change their plan. They expect to keep the fed funds rate at a relatively high level at least through the end of the year. Fed officials would pivot to easier policy if they felt they had caused too much economic damage. By that time of course, the damage would be largely done.

Easier policy would likely have positive implications for financial conditions and therefore stock valuations. What the Fed doesn’t want to do is send an “all clear” signal to the markets that the liquidity taps are reopening, encouraging investors to speculate in loss-making businesses again. A resurgence of easy money would drive inflation back up. A comment from the December FOMC meeting minutes addresses this:

“…because monetary policy [works] importantly through financial markets, an unwarranted easing in financial conditions, especially if driven by a misperception by the public of the Committee’s reaction function, would complicate the Committee’s effort to restore price stability.”

A Game of Chicken

It’s a game of chicken. Fed officials are thinking the stock market will crack, reflecting lower expectations for future growth and inflation. The Fed seems to be girding for tough economic conditions. Investors are thinking the Fed will cave (cut rates). Political pressure for the Fed to ease will only mount if tight monetary policy is causing economic pain.

Even in a recession, the Fed will likely be far more measured in cutting rates because it doesn’t want easier monetary policy to contribute to a rebound in inflation. With the Fed reluctant to provide too much monetary easing, and for that matter, with a federal government reluctant to provide much fiscal support either, we probably would not see a rapid economic snapback. Under the yoke of still relatively high rates, economic prospects may be fairly subdued. The economy would of course recover, but at a more moderate pace. With our national debt at 120% of GDP, interest rates driving substantially higher federal debt service payments will further dampen economic prospects, having a most deleterious effect on our federal budget in the coming years.

Over the next business cycle, we are likely to see either inflation being higher than it has been, the Fed keeping interest rates higher than they have been, or some combination of the two. It seems unlikely that inflation will serendipitously return to a 2% level while real GDP growth returns to 2 percent.

What Does This Mean for Stocks?

Fed officials seem to feel the economy must endure a certain level of pain in order to fully expunge the specter of inflation. That pain is likely to be felt by investors as well as the economy more broadly. Corporate earnings, and by extension, stocks, can be more sensitive to changes in the economy than the labor market. We may endure an “earnings recession.”

At the time of this writing, the Wall Street consensus is forecasting S&P 500 earnings to grow just 4.4% in 2023, reflecting some economic slowdown, but earnings would likely fall outright if we were in a recession. Moreover, the S&P 500 Index price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio currently stands at 17.3x this consensus earnings forecast, which assumes growth. The ratio is 12% above its 20-year historical median, and would be lower if stock prices were anticipating a recession. In an environment of higher interest rates, P/E multiples are typically lower anyway, while real growth could very well be lower than it has been. Despite stocks facing some challenges ahead, and even though bonds offer more competitive yields than they have in a long time, we advise clients to stay invested in stocks for long-term capital appreciation. As always, we will continue to hunt for sources of outperformance while keeping a watchful eye on risks.

Easier monetary policy should usher in a better environment for stocks. The Fed will eventually pivot to easier policy, but they will pivot when there is enough bearish sentiment to offset the good news of the pivot itself. Buying stocks just before the pivot could prove very timely. The stage would be set for a more durable bull market if earnings expectations have been revised downwards to reflect weak economic conditions and tight monetary conditions.

The tidy script that stocks will rally after a pivot might work, but stocks have never been very good at following a script. Having invested through wars (Ukraine) and plagues (Covid-19), investors should know to expect anything. Stocks are risky. However, even in, or especially in, times of great uncertainty, long-term investors usually come out on top. Stocks can always surprise to the upside, and they are particularly prone to do so when the pervading mood is fearful. Having a sense of how the economy and financial landscape are likely to evolve can help us stay invested during difficult times, and may further help us to bias a diversified portfolio towards sectors and stocks that are more likely to outperform.

— Adrian G. Davies, President

________________________________________________

1 Conor Sen, “Recession Fears Find Relief in January Inflation Bump,” Bloomberg Opinion, 1/4/23.

2 The Fed has been informally targeting a 2% level for inflation probably since the late 1980s.