Woodstock Quarterly Newsletter / Q3 2019

The S&P 500 Index returned +18.5% through the first six months of this year, following a -13.5% fourth quarter of 2018. On a year-over-year basis, the market has returned a still strong, but more modest +10.4%. The market hit a rough patch in May, down 6.4%, when trade negotiations between the US and China stalled. Also in May, the Trump Administration imposed more aggressive sanctions on China’s leading telecom equipment manufacturer, Huawei, and threatened to impose tariffs on Mexico. Tensions with Iran rose as the oil-producing nation threatened to violate its nuclear non-proliferation agreement with the West, and concerns over greater government oversight rattled Technology stocks. Despite the geopolitical and regulatory issues largely remaining, the market recovered 7.1% in June on hints the Federal Reserve might start cutting interest rates. Investors are evidently quite pleased with the business outlook overall given that the stock market has been hitting new all-time highs and trades around 16.7x forward earnings.

Bond yields have been falling

While the stock market has been rising this year, bond yields have been falling. The 10-year US Treasury yield has fallen from 2.69% at the beginning of the year to 2.00% at the half-way mark. Interest rates have been trending downwards for 39 years, but US rates remain high relative to other countries’ sovereign debt. Although the US 10-Year Treasury yield hit an all-time low of 1.37% in July 2016, the European Central Bank set its Main Refinancing Operations rate at -0.40% in March 2016, and longer maturity European bonds have followed suit. The yield on the German 10-year Bund closed the most recent quarter with a yield of -0.33%. In Japan, 10-year Government debt yielded -0.16%. There’s even some high yield debt with negative yields. If that doesn’t make any sense, it shouldn’t. Negative rates run contrary to most everything we learned in finance – investors would be better off holding cash than investing in bonds with negative yields. US yields are more rational than rates elsewhere in the world, which is a positive.

Negative rates have been part of the investing landscape since 2014. Factors in place for many years which have driven yields lower and bond prices higher include aging demographics, wealth inequality, globalization, and technological advancement. High outstanding debt levels slow economic growth, which may paradoxically drive interest rates lower as well. Over this cycle, the Fed has continually lowered its estimate of the long-term neutral interest rate, a rate which neither contributes to nor detracts from economic growth. Although these considerations are all important, they probably aren’t responsible for the more rapid decline in rates which has occurred so far this year.

This year, bond investors are reacting to slowing global economic growth, the increasing risk of a recession, and capitulation that central banks haven’t been able to increase inflation. Taking its cue from longer-term rates, the Fed is cutting the federal funds rate for these reasons, and because the relative strength of the US economy has put the Fed at odds with other central banks. Foreign central banks have continued easy monetary policies. Since the Fed was one of the only central banks tightening, the US Dollar has been strengthening, making it more difficult for US manufacturers to export. In addition, the US Treasury yield curve inverted, which historically has been a strong indicator that a recession is coming.

Economic growth has slowed

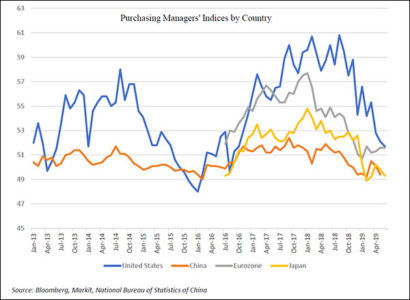

The US economy has now tied the record for its longest economic expansion at 10 years. The previous record expansion ended in March 2001. Whether or not the end of this cycle is imminent remains debatable, but we are definitely late in the economic cycle. While some economic statistics remain robust, others are weakening. In particular, the US Institute of Supply Management Purchasing Managers’ Index and business spending have been slowing. Around the world in fact, purchasing managers indices have been declining (See chart). Growth may be slowing globally for a myriad of reasons, one of which is the additional uncertainty introduced by trade tensions.

Slowing purchasing managers’ indices don’t necessarily mean we are heading into a recession — business orders could easily reaccelerate. In the US, business spending is weak but consumer spending remains strong. One bullish scenario for stocks is that the trade war is resolved and economic growth reaccelerates with limited inflation.

US real GDP grew 2.1% in the second quarter, while US unemployment was 3.7% in June, the lowest it has been since 1968. Ordinarily, the scarcity of workers would drive wage rates up. Wages grew 3.1% year-over-year, which is encouraging but also significantly below growth rates at other times unemployment has been low, and down from +3.4% in February. There are differing explanations for why low unemployment hasn’t driven wage growth higher. One important factor is that the unemployment rate only counts individuals actively looking for work. The participation rate, which measures the size of the workforce relative to the total working-age population, stands at 63.0%, below the 66%-67% range where it stood for most of the 1990s and 2000s. The low participation rate suggests more people are out of work and not looking for work. To the extent that these people can be enticed back into the workforce, the economy has additional growth potential.

Capitulation on inflation

Throughout this economic expansion, the Federal Reserve has consistently overestimated the threat of inflation. The Fed raised the federal funds rate four times in 2018 and nine times so far this cycle in anticipation of higher inflation which by and large has not materialized. There were widespread expectations in 2018 that the Trump Administration’s tax reforms would stimulate growth. The Fed raised rates fearing that the economic acceleration would stoke inflation. Now that growth is slowing down, those rate increases appear to have been unnecessary. Long term bond investors evidently have given up on inflation as well, driving 10-year Treasury yields below the current core CPI, which was up +2.1% in June. In his July Congressional testimony, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell expressed concern, saying low inflation is “one of the major challenges of our time”[1]. It is ironic then that the Core Consumer Price Index (CPI ex food and energy) is actually above the Fed’s 2% target. The headline CPI and the core Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index are still below target, both at 1.6%, but one wouldn’t think this condition rose to quite the level of importance articulated by the Chairman.

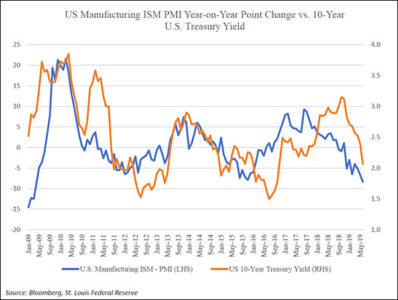

Inflation and real economic growth often rise and fall together, so it’s probably worth tolerating some inflation in order to have better real growth. However, in the past few years, whenever economic growth has accelerated, interest rates have risen, and the higher interest rates have dampened economic growth. This happened in 2010, in 2013, and again in 2018 (See chart). So the economy has not been able to break the cycle of accelerating growth increasing interest rates and higher interest rates limiting economic growth.

Fears of stoking inflation have been the main concern preventing the Fed from using monetary policy more aggressively. If monetary stimulus isn’t putting the economy at risk of overheating, their thinking is that they should continue to stimulate. Weak global demand and the strong US Dollar have kept a lid on inflation, but these conditions won’t always hold. At some point, global aggregate demand will strengthen and inflationary pressures could rise.

Yield curve inversion

The 10-year US Treasury yield dropped below the 3-month Treasury Note yield in late March. After recovering briefly, it fell below the 3-month yield again in May and stayed there through June. The yield curve inversion – longer term rates below short-term rates – is an indicator suggesting that the economy will enter a recession within the next year or two. Inversion is also an indication that the Fed’s monetary policies are too tight, at least relative to the long end of the curve: if we are about to enter a recession, the Fed probably should be easing. An inverted yield curve squeezes bank profits.

Although Chairman Powell hasn’t emphasized the yield curve specifically as a reason for cutting interest rates, business leaders are well aware of its somber omen. Long rates are generally set by market forces based on comparable investment opportunities whereas the short end of the yield curve is mostly controlled by the Fed. The indicator isn’t infallible, and could be distorted by negative rates overseas. Even if we have a recession, it’s possible that it is mild, unlike the one we saw in 2007-2009. Consumers aren’t driving a debt-fueled consumption boom as they were preceding the Great Recession. But if a recession follows this yield curve inversion, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) members don’t want to have sat by passively and let it happen. By cutting rates, they may normalize the yield curve, putting the economy on course for better long-term growth.

A

A stock bubble and a recession, or the other way around

On the face of it, the Federal Reserve members should congratulate themselves. They have largely achieved the central bank’s dual mandates of maximizing employment while maintaining price stability. Yet beyond that, matters aren’t so clear. The Fed is cutting rates at a time when stocks are at all-time highs and above-average valuations; long-term yields are close to all-time lows; unemployment is at 50-year lows; and we are running $1 trillion Federal deficits after 10-years of economic expansion. Monetary policy has been fairly easy since the Great Recession, yet interest rate cuts and quantitative easing have had only a modest impact on inflation. Overseas, negative interest rates have failed to stimulate economic growth or incite inflation. Investors’ faith in the US Dollar seems unshakeable, but that is because major central banks are all pursuing aggressive monetary policies at the same time. The US Dollar may be the best house in a bad neighborhood, and we need to monitor the whole neighborhood.

In June, the FOMC modified its regular meeting statement to say the committee would “act as appropriate to sustain the expansion.” Powell underscored this in his testimony to Congress, saying “It’s very important that this expansion continue as long as possible.”[2] To be sure, we would like the current economic expansion to continue as long as possible. Although monetary policy might be able to squeeze out more growth than the natural course of the expansion would otherwise allow, extending the expansion would mean taking monetary policy to further extremes. Aggressive policies could exacerbate the business cycle. The economic slowdown from overstimulated conditions would be all the more dramatic.

Loose monetary conditions have already pushed the prices of both stocks and bonds higher. Fears of a recession or market crash may be keeping some investors away from stocks, shifting funds into bonds. The result, from our perspective, is that bonds have strayed much further from their historical averages than stocks. When there is a recession, stocks will still get hit, but that would be a buying opportunity.

The Fed will respond and the economy will recover. Given the Fed’s willingness to ease now when many economic indicators are fairly strong, they are likely to get all the more aggressive if the economy were to turn down more definitively. John Williams, the President of the New York Federal Reserve, recently said that “central banks should take swift actions against adverse conditions.”[3] Central bankers probably should be more concerned that even if loose monetary policy doesn’t generate inflation, it could inflate asset prices to unsustainable levels.

William McChesney Martin, the Fed Chairman from 1951 to 1970 felt it was the Fed’s job “to take away the punch bowl just as the party gets going.” This Fed wants to keep serving punch, although to be fair, they were tightening when most other central banks kept easing. The Fed may feel forced to cut rates in response to global economic weakness. Within the next cycle, the federal funds rate is likely to return to zero if not go lower. Keeping with the punch bowl analogy, the Fed wants you to know they’ll be serving even more punch the morning after.

Monetary stimulus might not be as efficient an economic tool as we would hope. A criticism of Fed’s previous quantitative easing programs is that they disproportionately benefited the wealthy by raising asset prices. If stimulus affects asset prices but doesn’t lead to upward pressure on wages, that would explain why inflation is muted. The next quantitative easing program could very well be coupled with fiscal spending or tax vouchers in such a way that its benefits would be more broadly distributed. Broader distribution is more likely to stir up inflation.

A

Stock picking

Most of financial theory is based on the idea that money is a scarce resource. Under a loose monetary regime, companies don’t need to husband cash because they can easily raise more. Companies’ current ability to generate profits, and measures of valuation based on profits, become less important than their ability to grow. Uber and Lyft, two growth stocks which became public companies this year, and which are not Woodstock recommended investments, are reporting billions of dollars in losses while investing to grow. If monetary conditions were more restrained, these companies wouldn’t be able to support business plans involving multiple years of large losses. Fed policy is enabling these businesses to grow, but any number of companies can grow simply by throwing money at their problems. Inefficient companies can undercut well-run businesses and take market share. Companies with abundant cash don’t have to make hard decisions — financial discipline can be cast aside as long as there is promise of future profits.

On the whole, Woodstock clients have participated in the market’s gains with high quality growth stock exposure. We invest in stocks with solid growth potential, but which also have a proven ability to generate profits and cash flow in a disciplined manner. To the extent that current market conditions don’t appreciate the importance of current profitability, we believe these attributes will return to relevance in the fullness of a market cycle.

We’ve attempted to describe a number of cross-currents prevalent in the markets and economic landscape today which could lead to a range of possible financial outcomes. There are plausible scenarios under which the stock market both rises and falls. What we can be sure of is volatility. Woodstock’s strategy of investing in high quality stocks has proven to be a reliable method of dealing with market uncertainty in the past, and we believe it will continue to be so going forward. We will continue to favor stocks with both strong and growing cash flows.

Adrian G. Davies is Executive Vice President at Woodstock Corporation.

You may contact him at adavies@woodstockcorp.com

[1] Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, Semiannual Monetary Policy Report to the Congress, 7/10/19. www.federalreserve.gov

[2] Federal Reserve, Op. Cit.

[3] Cox, Jeff, “Fed’s Williams hints at more aggressive rate cuts: ‘Better to take preventative measures,’ CNBC, 7/18/19.